By hook or by cook: This duo is trying to build a 'healthy' food empire

Cure.Fit co-founders Mukesh Bansal and Ankit Nagori see great potential in healthy foods

Mukesh Bansal (left) and Ankit Nagori, Cure.Fit co-founders, are excited about the humongous potential of the healthy food industry

Image: Madhu Kapparath

Ten years ago, Sudhir Sethi trusted his instincts, rather than logic that venture capitalists usually rely on, to back a rookie entrepreneur.

It was November 2008. A fledgling Bengaluru-based startup that sold customised gifts and merchandise, Myntra Designs, raised $5 million in a series A round of funding. Venture capitalist firm IDG Ventures was one of the lead investors. Sethi of IDG Ventures, who joined the Myntra board, was confident that he had bet on the “right” man, who had spent a good part of his career in Silicon Valley.

Fast forward to 2018. In July, Sethi was once again one of the lead—and existing—investors behind a $120 million series C round of funding in health care startup Cure.Fit. Its co-founder was the same rookie entrepreneur and “right” man who Sethi had backed a decade ago: Mukesh Bansal.

“Bansal has always been either on time or ahead of the times,” contends Sethi, one of the first investors in Myntra, which started as a customised merchandise gifting outfit in 2006. Within 18 months of raising the money, Myntra pivoted to online fashion, says Sethi, who knows Bansal since 2007. The gross merchandise value that the startup was clocking at the time of pivot, Sethi recalls, was roughly ₹12 lakh per month. In 2014, when Flipkart bought Myntra, the online fashion retailer had a run rate of over $100 million.

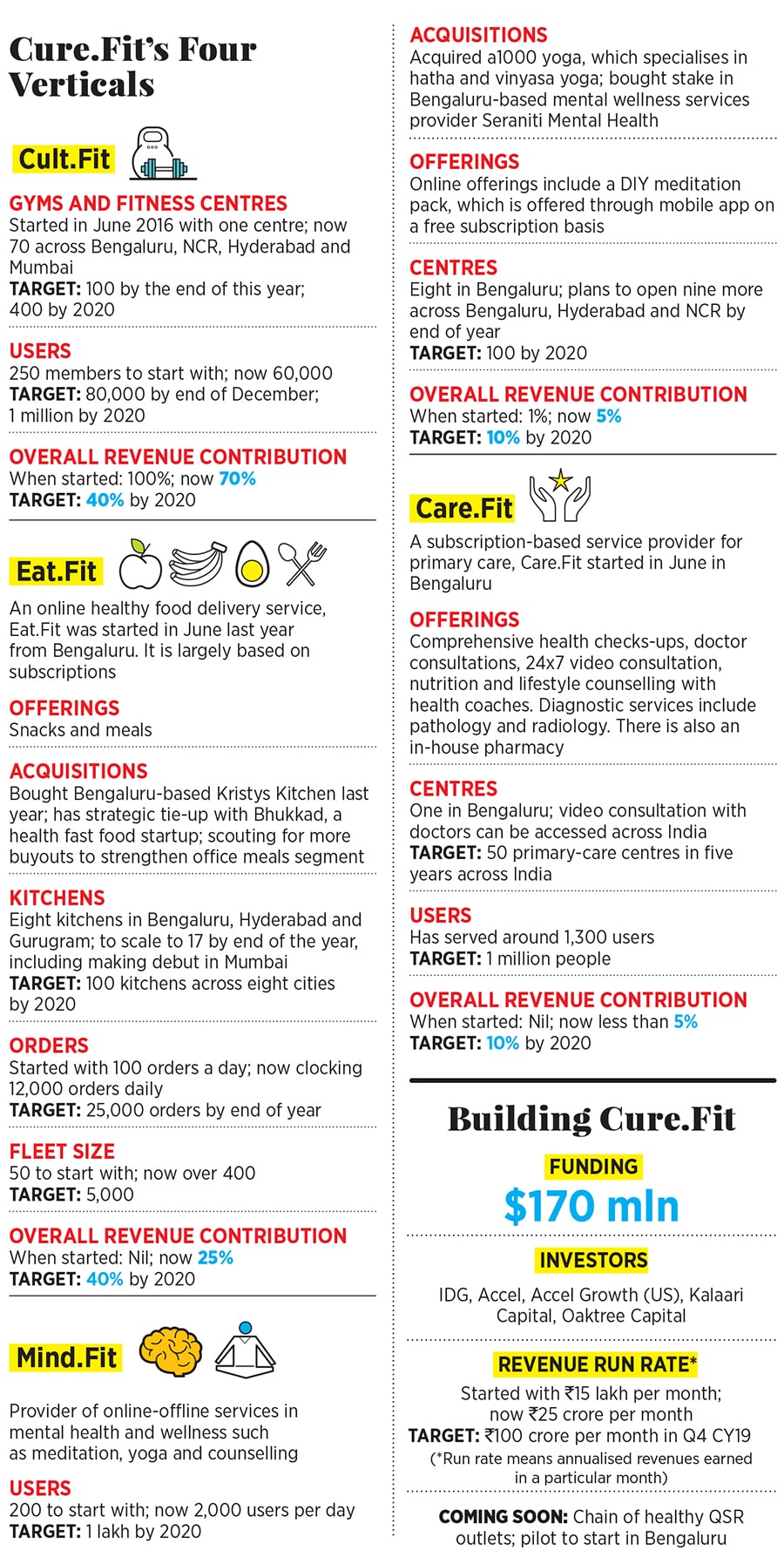

Starting with a single kitchen in Bengaluru last June, Eat.Fit has opened eight kitchens across Bengaluru, Hyderabad and Gurugram. It claims to clock over 12,000 daily food orders and has a delivery fleet size of 400. The immediate target is to reach 25,000 daily orders by end of this year. It’s the plan for 2020, however, that’s audacious: 100 kitchens across eight cities, deliver a billion meals, increase the fleet size to 5,000, and make the food division the biggest revenue contributor among Cure.Fit’s four verticals the other three are Cult.Fit, Care.Fit and Mind.Fit (see box).

The Bansal-Nagori duo is simmering with plans to build a health food empire in India, a gambit that hasn’t been tried so far. Sethi reckons it’s one of a kind internationally, too. “He (Bansal) knows how to build, execute and scale. Cure.Fit is a unique business model globally,” says Sethi, who is once again betting big on the domain “inexperience” of Bansal, 42, and Nagori, 32, to strike gold with Eat.Fit and its ambition to roll out a chain of healthy quick service restaurants (QSR) in India.

SERVING HOT

On a muggy August morning at the Grand Mall in Gurugram, Bansal and Nagori are busy overseeing operations of the latest Eat.Fit kitchen. Although centrally located on MG Road, the 5,000-sq-ft kitchen is inconspicuous. Reason: It’s in the basement of the mall. Hemmed by a few brand outlets and thronged by deal-hunting consumers, Eat.Fit looks visibly calm from the outside. Step inside and it’s a different story. On the right side is a long, narrow room filled with scores of delivery boys. Big, blue Eat.Fit and Cure.Fit food bags are neatly stacked in one corner. Edgy delivery boys ask for their delivery packs from small windows marked as ‘dispatch stations’.  Bansal, in a light-grey T-shirt, blue jeans and bouffant cap, inquires with his chefs about the following day’s breakfast menu. He’s also curious for more details about meals. One chef fills him in on the Dilli egg parantha and tomato chutney. One of the non-veg breakfast options, it is priced at ₹69, and loaded with 417 calories, 26 gram protein, 13 gram fat and 51 gram carbs.

Bansal, in a light-grey T-shirt, blue jeans and bouffant cap, inquires with his chefs about the following day’s breakfast menu. He’s also curious for more details about meals. One chef fills him in on the Dilli egg parantha and tomato chutney. One of the non-veg breakfast options, it is priced at ₹69, and loaded with 417 calories, 26 gram protein, 13 gram fat and 51 gram carbs.

The food, the chef lets on, is made from 100 percent whole wheat, contains gluten, dairy and eggs, and uses no preservatives. For vegetarians, there is a raisin pop oatmeal bowl—apart from other breakfast options—that contains 379 calories, 11 gram protein, 6 gram fat and 70 gram fat.

“Nobody has ever gone into so much of detail and planning,” claims Bansal. From using antibiotic-free chicken to low-fat, lactose-free artisanal yogurt raita to no-butter and zero-cream palak paneer for meals, Eat.Fit is trying to make a healthy diet as readily available as any other regular cuisine. Food, Bansal adds, is the fastest growing segment of Cure.Fit.

Nagori steps in to explain why. “We are making a healthier version of what one eats every day,” he says. All diet plans, Nagori adds, start and end on paper. Although users are eager to follow a diet regime, they struggle to make such food at home or get it from outside. “That’s the pain point we are trying to solve,” he says. A healthy lifestyle is incomplete with just exercise. “Without a healthy food regime, nothing will work,” he avers.

Though the duo planned to add healthy food under Cure.Fit when the startup was launched, the process got accelerated after feedback from the users of Cult.Fit, which offers fitness classes. People, Nagori recounts, lamented that a lack of healthy food options was putting paid to all efforts at staying healthy. “It’s not just the calories, but also the quality of the calories that matter,” Nagori explains.

HEALTH IS WEALTH

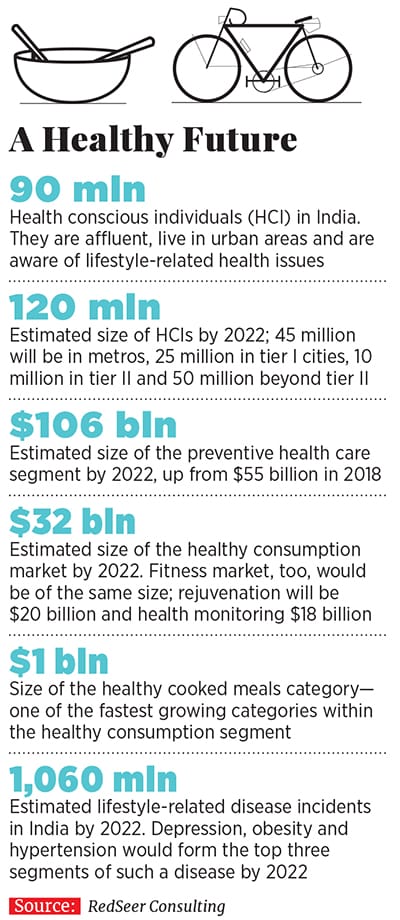

The business opportunity is huge. From $55 billion in 2018, the preventive health care segment in India is pegged to reach $106 billion by 2022, according to research firm RedSeer Consulting. The healthy consumption segment, its report predicts, would grow to touch $32 billion in four years.

The Blue Ocean marketing theory, postulated by professors W Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne of Insead in the early 2000s, states that companies can make competition irrelevant by not fighting with them, but by hunting for a Blue Ocean, or uncontested market space. That makes more sense than struggling for survival in a Red Ocean swarming with competitors.

Bansal compares the stage of this opportunity with online fashion a decade ago. “The idea of selling clothes online was at a nascent stage,” recalls Bansal. Many scoffed at the idea. Giving a healthy spin to regular meals, he lets on, again is something that not many are into and none at the scale that Eat.Fit is planning. The same logic explains the move to enter into the healthy QSR space. A pilot QSR outlet will be launched in Bengaluru in September.

Eat.Fit, explain experts, is making a bold move of treading into an area that’s been largely unexplored. All the fears surrounding food, maintains Jaspal Sabharwal, a private equity veteran and co-founder of online community for food professionals TagTaste, can be traced directly to the rise of processed food, rampant use of pesticides in farms, lots of cheap fat, sugar and salt.

“Look at the framework of our labels and claims on the packaging. One needs a scale, a lens and a calculator to make any sense out of them,” he says. Eat.Fit, Sabharwal adds, understands the importance of transparency, value-centric mass solutions, and emotive-economic accountability.

However, there might be hiccups. Although an increasing number of urban Indians are turning orthorexic—people with an unhealthy obsession with healthy eating—this segment is extremely volatile in its expectations. “They embrace organic food but still expect a global array of products, despite natural differences in season or geography,” says Sabharwal.

Eat.Fit, Sabharwal points out, is a powerful proposition as long as Bansal and Nagori don’t misjudge the might of their delivery model as a sign of food differentiation. “These two aspects are completely different,” he says, pointing out another potential problem area: The back end of the business.

Cure.Fit’s presence in multiple health care verticals might rob it of a focussed approach and spread it too thin. Scaling up the food business while fixing ingredient sourcing, culinary intelligence, logistics, consistency in quality, consumer insights, and cooking technology might take a toll, warns Sabharwal.

Bansal and Nagori prefer to remain focussed on the goal. “The healthy food industry is humongous. We can easily achieve a million daily orders in three years,” says Bansal. “The biggest challenge is meeting the demand,” chips in Nagori.

Now that’s healthy food for thought.

First Published: Aug 31, 2018, 11:54

Subscribe Now