Aerospace Engineering Firm Quest Global's Changing Lanes

Aerospace companies move from manufacturing to services. But Quest Global has taken the opposite route. Can one feed into the other to beat competition?

The skies over Bangalore’s Yelahanka airbase thundered with the sound of fighter planes, helicopters, turboprops and other aircraft. As the biennial air show—its 2013 edition in February is considered Asia’s biggest-ever aviation event—was in action, one aircraft had a different flight path: Business jet Embraer Phenom-100 made chartered flights to Belgaum. Perhaps it was the right time for Quest Global Inc to show potential customers that the aerospace hub it has been building is ready for take-off.

On the outskirts of Belgaum, nearly 500 km from Banglaore, is the 300-acre special economic zone (SEZ) set up by Quest. Driving through the beautiful landscape, it is difficult to believe it could soon be the most sophisticated industrial belt in the region. It is already notified as the state’s first precision engineering region. “You can walk away from this place with a finished [aerospace/automotive] product without stepping out of this facility,” says Aravind Melligeri, co-founder and chief executive of Quest Global Inc, the manufacturing arm of Quest Global Engineering.

No other facility in India, other than state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics, can claim such a design-to-build capability in aerospace. “It is built very neatly, in a graded manner,” says Ashok Baweja, former chairman of Hindustan Aeronautics.

Over the past four years, Quest has developed essential capabilities of an aerospace cluster, such as machining, surface treatment, forging and assembly. It has done some on its own for others, it formed joint ventures with overseas partners: Magellan Aerospace of Canada, Saab of Sweden and Aubert & Duval of France. The ventures are to serve the global supply chain, although India’s share in the $100 billion commercial aerospace manufacturing is a paltry $100 million.

It was the 2005 defence offsets policy that turned things on its head. Most industrial groups, including the Tatas, Mahindras and L&T, formed partnerships and talked big investments. Looking back, it appears they moved opportunistically. “Even the human resource deployment was convenience-based,” says a public sector aerospace official who saw automotive professionals handling aerospace projects. Three SEZs, two in Hyderabad and one in Bangalore, were also announced.

This February, Karnataka announced a 10-year aerospace policy, which will target $10 billion in investment. It also announced a 1,000-acre industrial park near its SEZ. Even if one considers all this to be hot air, it remains plausible for states to roll out the red carpet for big companies.

Additionally, the conglomerates are finally getting a hang of this high compliance industry. Mahindra Aerospace’s first greenfield project is nearing completion in Kolar. With competition soaring, can Quest create an aerospace cluster in Belgaum, like Toulouse near Paris or Wichita near Kansas City?

Melligeri has bet his life he can.

The Bug of Business

As a child, Melligeri knew he had to get higher engineering degrees from the US. No sooner did he get there that he knew he had to start his own business, even abandoning his PhD programme. It took him a while to find an entrepreneurial young engineer to team up with. Ajit Prabhu, co-founder and chief executive of Quest Global Engineering, was also looking for a like-minded partner.

Prabhu landed himself at the GE R&D centre near New York soon after graduating. He had to pay off the debt he incurred on his credit card while paying for his parents’ US visit. At GE, the engineer in him felt like a “kid in a candy store”, but the businessman in him kept bugging him. Every time his manager cribbed how contract agencies couldn’t find the right skills for the company, Prabhu knew his business idea lay right there: An engineering services company.

At GE, Prabhu did structural analysis of gas turbine rotors Melligeri modelled the impact of automotive crash at Ford in Detroit. Just over two years into their jobs, in 1997, they decided to borrow money on their credit cards and register Quest Engineering in New York. It was registered in India the following year. In the first year, Quest made $300,000. All the projects that Prabhu had worked on at GE eventually came to Quest, even though his manager thought starting a company “was the stupidest idea”.

By 2001-02, the company was grossing $20 million. Prabhu, who sold incense sticks as a schoolboy to get a sense of business, found more projects coming his way than he could handle. And then Enron—the energy trading giant—collapsed. Several GE power generation contracts got cancelled. Quest, which got 80 percent of its revenue from GE, saw revenue dip to $14 million, and GE’s share in it fell from $18 million to $6 million.

“We shrank that year, first time in our 16-year history,” grimaces Prabhu. To lay off people who had helped build the business was painful. “I lost lot of my hair, I grew up that year.”

But the experience was a turning point. In 2004, Quest decided to diversify and made its first five-year plan. It got other customers, like Pratt & Whitney, Rolls Royce, Boeing, Airbus and others. According to the plan, the business had to grow from $20 million in 2005 to $100 million in 2010. Coming out of the near-death experience of 2003, many thought “I was smoking”, guffaws Prabhu. But the entire team came around it. Quest totalled $98 million in 2010.

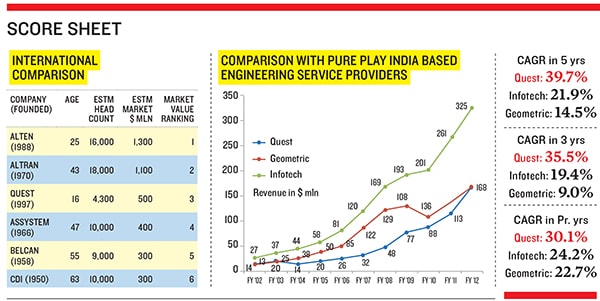

The scorching growth rate continues. From $235 million in 2013, it hopes to gross $500 million in 2015. More than half of Quest’s services business comes from aerospace. According to Nasscom data, most Indian IT services companies are growing this business at 18 to 20 percent, but Quest is clocking 40 percent.Reasons for its performance are many. It has a few customers, but its relationships are strategic. Company processes are geared towards understanding these customers. Quest even recruits from among customers. “We are not order takers,” says senior vice president Raman Subramanian. For instance, when Quest saw Pratt & Whitney and a few other companies build a backlog—new products waiting to get into manufacturing—it invested in strengthening its supply chain management expertise. “We saw the pattern, took this call and told the customers we can do it,” says Subramanian.

To serve global customers, Quest has adopted merger-and-acquisition-based growth. The market is worth $70 billion, but is severely fragmented. In future, Prabhu believes, customers will not only outsource more, but consolidate their buy with a few companies who have the “technical competence to do bigger things”. Its acquisitions in the US, Spain, and Australia are in response to these trends, and have been integrated into Quest’s core business. No engineering services company has done it so early in its life cycle those who have acquired overseas, did it as a late reaction. It’ll be apt to say its middle name ‘Global’ symbolises its ‘DNA’, a metaphor Prabhu is fond of.

But Prabhu says he has more questions than answers. Like many first-generation entrepreneurs, he sheds the corporate veneer when deep in conversation. “It’s possible that I am blind-sided… not seeing what could disrupt [the business].” Truth is it is organisational development he obsesses about. If an organisation grows at 5 to 10 percent, people adapt but if it grows at 100 percent every two years, how do you make employees grow that fast? He thinks training programmes don’t work. “You have to have experiential development which may, in normal course, take 10 years. How do you do that in two years? If you get people from outside, it works for two years and then they face the same challenge.”

Growing the pie

Around mid 2000s, when Quest made its first five-year plan, the founders went through a painful process of diversification. Manufacturing, though different, provided some synergy with engineering services. Melligeri was also passionate about it. But it was perplexing to many, including their private equity investor Carlyle, whose equity Quest bought back later. But Prabhu and Melligeri invested $2 million in a “small shop”. Today the business has $50 million in investment, mostly the promoters’ money. The manufacturing arm earned $12 million in 2013 and will close 2014 with $22 million in revenue. It has twice that amount as committed investments from joint venture partners. By 2016, when Singapore-headquartered Quest Engineering plans to go public, Quest Global Inc expects to clock $100 million in revenue.

That’s impressive, because most companies that started at the same time have had teething, and tooling, issues, which Baweja calls “cultural”, because the Indian industry is not used to strict rules of operation that aerospace requires. The Tata-Sikorsky joint venture in the Hyderabad SEZ, designed to supply cabins to S-92 helicopters, has had a backlog. The manufacturing has recently gathered speed. “It took us 10 months to produce one cabin, now we are producing three a month,” says Air Vice Marshall (retd) Arvind Walia, executive vice president for India and South Asia, Sikorsky. Components were initially imported now 80 percent is produced by the joint venture.

Another reason for the sluggish start is that most government defence acquisitions have been delayed so, contracts aren’t really awarded. Also, says Nidhi Goyal, director at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India, business in this sector requires approvals and licences from various ministries before and after awarding the contract.

Quest, meanwhile, is listing itself as offsets partners of large aerospace companies. It has listed with Dassault and Safran, which, between them, form nearly 65 percent of the medium multi-role combat aircraft Rafale that India is buying from France for $10 billion. Till offsets start flowing, Quest is stitching other deals.

Magellan Aerospace was on the verge of ending sub-contracting of machine parts to India. It needed a surface treatment plant but the question was where to build or find one. Belgaum was a perfect fit. The location might be remote, but Quest makes “everything so easy”, says Konrad Hahnelt, vice president of North American Operations at Magellan. “They have their own municipality, customs… it mimics a Western set-up of an aerospace business,” says Hahnelt. He thinks more Western companies would come to Belgaum when they see what it has to offer. Two automotive companies have come in and many others, including the Tatas, are sending their parts to Belgaum for treatment.

Hahnelt thinks some of the “large joint ventures [in India] have taken big risks”. “Aerospace is not about setting up million square-feet facilities, but getting it right for the severe quality restrictions that this industry has.” Magellan has been in India for 10 years. It took two years to ship its first component today it ships 150,000 to 200,000.

To address all this, Melligeri has two strategies: Form horizontal joint ventures to build new capabilities, like casting and composites and vertical partnerships to scale manufacturing, such as that of aero structures and aero systems. He knows that once the structures reach a certain size, shipping cost would become prohibitive. “We’d then acquire companies overseas and do back-end work in Belgaum,” says Melligeri, replicating what the parent company has done in services. It has bought a small facility in Houston for making oil and gas components. Unlike China, where in-country manufacturing adds only 5 to 10 percent in value, Quest, and other Indian companies, will have to do 50 to 60 percent value addition.

It was the same high value addition that Quest did in engineering services. Nearly 80 percent of its customers in manufacturing are also customers in engineering services. One follows the other. For instance, in Toshiba and Baker Hughes, manufacturing contracts came first for Airbus, engineering came first.

What if this model gets disrupted? What if the government rolls out the red carpet to big companies, in Bangalore or Hyderabad?

“The government has no red carpet to roll,” Melligeri says, half-smiling. He narrates how a customer, who could have brought nearly $1 billion in revenue, wanted to come to Belgaum but needed some cushion to save it from transition costs. The Karnataka government could only offer reimbursement of apprentice cost. But Malaysia rolled the red carpet out and the customer went there. “My facility guarantees 100 percent uptime a building to one’s specification on lease which a company can operationalise in six months… Which SEZ can offer these?” he asks.

To grow the aerospace pie further, Prabhu and Melligeri floated yet another company in January: Quest Global Defence. Purely looking at offsets opportunities, it will expand the engineering services business in aerospace and defence from the original equipment manufacturers. With none other than erstwhile HAL chairman Baweja as its head, the new entity has already signed his first modest contract.

Strong tail winds are expected. Deloitte forecasts growth in commercial aircraft manufacturers’ revenues will reach record levels in 2013. It is also the third consecutive year of global production levels above 1,000 aircraft per year.

“We have plenty of runways,” says Prabhu. For Melligeri, the path he wants to walk down is laid: “I grew up in [north Karnataka] and I will retire there. That’s why I want to grow the Belgaum facility. This is the biggest differentiator between other SEZs and ours.”

First Published: May 14, 2013, 06:58

Subscribe Now