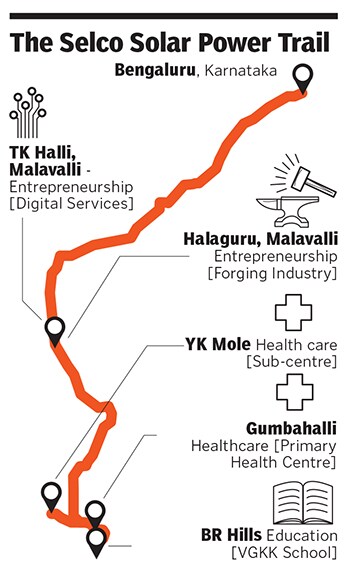

Selco Foundation: Using solar energy to foster entrepreneurship

The Selco Foundation has been using solar energy to empower lives and foster entrepreneurship among rural communities across India

Solar power panels help rural communities set up and scale their commercial ventures

Solar power panels help rural communities set up and scale their commercial ventures

Image: Leisa Tyler / Lightrocket via Getty Images[br]Almost 107 km from Bengaluru is the village of TK Halli, in Malavalli taluk, that houses a single photocopy shop. It’s at the end of the lane I was standing in, I was told. But what I found instead was a home from which a teen walked out and ushered me into a hall that had a TV set and three plastic chairs. The only semblance of a commercial establishment came from the solar-powered photocopy machine that stood next to the TV. It was indeed the local “xerox shop”, but unlike any I’ve ever seen.

Despite the unusual setting, the photocopy services that Maurya, the 18-year-old, provides at his home are as good as any: ₹2 for a black-and-white copy and ₹10 for a coloured one. “Earlier, we had to travel a lot just for a photocopy, which made it even more expensive. Electricity was unreliable, and the shops would charge us more when there was no power—₹5 per copy instead of ₹2. Now people from other villages come here, since we have electricity 24x7,” says Maurya.

The turnaround took place about a year ago when Maurya’s family bought the machine through a loan of ₹30,000 provided by the Shri Kshethra Dharmasthala Rural Development Project. The entire package to set up the photocopying facility—printer, solar panels, battery and the DC-AC converter—costs about ₹20,000. “We have already repaid the loan and have been making an extra income of ₹2,500-3,000 every month,” says Maurya, a civil engineering student who plans to invest in a solar-powered A3 machine soon.

The solar-powered machine has been set up by the Selco Foundation, the non-profit wing of Selco India, a sustainable energy enterprise based in Bengaluru. So far, the foundation has installed over 100 such machines in villages across India. And this is only one of the initiatives it has taken up to improve the lives of people in rural India.

Selco India was co-founded by Harish Hande in 1994 to decentralise energy solutions and implement them across geographies and socio-economic backgrounds. Hande set up the foundation in 2008 to create an ecosystem in rural India that would enable enterprises to flourish and innovations to be scaled and sustained. “We are working on how to democratise energy in a way that services can be delivered to the doorstep of the poor, and that which is financially sustainable from their perspective, not ours,” says Hande, a Ramon Magsaysay Award-winner. A blacksmith uses a solar-powered electric blower

A blacksmith uses a solar-powered electric blower

Image: Courtesy Selco[br] One of Selco’s most successful innovations is the solar-powered fan blower used by blacksmiths to keep the fire burning while forging metal. Says Siddhapaji, who has a small workshop in Halaguru village. “Earlier, I had to hire another labourer to help me blow the fire because it is a tiring task. My workshop didn’t have electricity, so I couldn’t buy an electric blower. Now with the solar-powered blower, I can take more orders as well as save the cost of paying for extra labour,” he says.

The biggest challenge for working in rural India is the hierarchy of education created by society, says Hande. “We treat the poor as beneficiaries, not as partners. If you and I spend two years doing a PhD on sugarcane we’ll be called experts. But a farmer who has spent 45 years cultivating sugarcane will never be called an expert.” Selco looks to break down these barriers by empowering the bottom of the pyramid through sustainable measures. “We want to use solar energy as a form of social catalyst to democratise society.” Malavalli—a 100 percent solar-powered taluk—is just one of the examples in the state. The Light for Education programme provides each student a portable solar lamp and battery

The Light for Education programme provides each student a portable solar lamp and battery

Image: Courtesy Selco[br]Inside the BR Hills Forest Reserve, about 170 km from Bengaluru, is the Vivekananda Girijana Kalyana Kendra (VGKK) campus that houses a school and a hospital. The region has been home to the Soliga tribe for hundreds of years now and VGKK has been working for decades to improve their living conditions. Selco launched its Light For Education programme here to get Soliga kids to attend school.

As part of the programme, each student is provided with a portable lamp and a battery for a one-time deposit of ₹200. “The students leave the lamp at home and carry the battery to school. Only the schools have solar-powered charging stations, not homes,” says Dipayan Sarkar, head of the design department at Selco Solar Light. Inspired by the mid-day meal scheme, the programme aims to ensure the students come to school every day to have light at home later in the day.

“The battery lasts for not more than two days. So children are forced to come to school every alternate day,” adds Sarkar.Headmaster Ramchar testifies: “The programme has helped improve results because kids can go back home and study. Attendance has improved as well.”

For a tribe that’s deeply entrenched within the forests of the region and has won a legal battle recently to stay within the core area of the tiger reserve, screens are a luxury. Selco chose to introduce Soligas to this bit of modernity through its Digital Education programme. “Often teachers can’t come to school on those days we bring children from Class 5 to 7 to the auditorium and they learn through interactive classes on the projector,” says Ramchar of his 300 students.

Rewasa Nishchal of Tata Trusts believes sustainable energy sources like solar energy can significantly improve quality of life. “Clean energy presents an opportunity to develop scalable and inclusive solutions. In general, it gives more productive hours to the family for education and livelihood,” says Nishchal.

Around 27 km away [from BR Hills], at Gumbahalli village in Chamrajnagar district, is the first Primary Health Centre (PHC) in South India to be accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare. To an outsider, it might look like an average Joe’s house but for 22 villages, it is a safe haven from all kinds of illnesses: From a woman in labour to a cataract patient to one suffering from epilepsy. The Gumbahalli PHC, run by the Karuna Trust, tied up with Selco Foundation a few years back to turn it into a fully solar-powered centre.

“Earlier, our greatest challenge was the dependency on electricity. In this area it is very unreliable,” says Nagendra who runs the PHC. Electricity is especially crucial during cataract surgeries or while delivering babies. Sumitra, a nurse, says, “Before solar, we had to hold the torch in our mouth while delivering babies, especially when we were short-staffed. It would take time to turn on the generator as well. The whole procedure was tough while suturing.”

Over the past three-four years, not only has the number of patients risen, but electricity bills have also reduced significantly. This is despite the deployment of a number of modern gadgets like baby warmers for newborns or a refrigerator to store vaccines. “Earlier,” says Nagendra, “these expensive machines would get damaged due to constant voltage fluctuation.”

In YK Mole, a village only a few kilometres away from the Gumbahalli PHC, is a sub-centre (the first contact point between the community and health services) that is a benchmark in design. Even in the late afternoon, it’s cool without a fan.

Sarkar of Selco explains, “The structure is made of low-cost material that is locally available. For sub-centres in the Northeast we use bamboo instead of reinforced cement concrete. It is also designed in a way that there is enough natural ventilation.”

Selco has also been making innovative forays in agriculture, the building blocks that make rural India. Some of its most popular inventions—like portable solar water pumps, head lamps, paddy thrashers and processing mills—improve efficiency, thereby raising incomes and better livelihoods of farmers in remote locations.

In Kariammanagar, in the Savdatti taluk, Patrappa Mahadevappa adopted Selco’s initiative to set up a solar-powered flour mill. He gets about 25 customers a day and earns about ₹400 per day. But, more importantly, the community members no longer have to make a 10-km trek to the nearest mill. “For solutions to be sustainable, they need to look at three aspects: Social, financial and technical,” says Hande.

Hande insists that these solutions come from rural entrepreneurs and not innovations sitting as prototypes in IITs. “We need to use the same decentralised approach to create hundreds of entrepreneurs across the country,” he adds. Unfortunately, there are barely any investors willing to fund them. “Out of frustration, we were forced to create an investment fund for rural entrepreneurs who were not getting private investment or couldn’t speak English to pitch themselves well. But, again, we only got money from foreign investors.”

First Published: Sep 20, 2019, 09:40

Subscribe Now