How to beat Bharat's blues

With rural consumers tightening their purse strings even for daily-use products, FMCG companies are trying to tide over the slowdown with a slew of strategies

Local variants like Dairy Rich cost ₹5 as against Dairy Milk’s ₹20 for the same size[br]Bhura Singh, 44, firmly believes that one cannot run a household by just being a grocer these days. He holds this view despite owning a large grocery store that caters to over 3,330 people in Khushhal Pur, Uttar Pradesh. The village has just one other store like his.

Local variants like Dairy Rich cost ₹5 as against Dairy Milk’s ₹20 for the same size[br]Bhura Singh, 44, firmly believes that one cannot run a household by just being a grocer these days. He holds this view despite owning a large grocery store that caters to over 3,330 people in Khushhal Pur, Uttar Pradesh. The village has just one other store like his.

Among the fastest-moving products in his shop are single-use tea packs by Nice (manufactured in the neighbouring Harpur city) priced at ₹1, noodles by Rafan (manufactured in Kanpur) priced at ₹5 and chocolates called Dairy Rich manufactured by a company called Appeal, costing ₹5. All these products are placed alongside Tata and Brooke Bond Taaza tea pouches, Nestle’s Maggi noodles and Cadbury Dairy Milk respectively. “Dehat mein kisi cheez ki kami nahin hai [Villages have many options to choose from]. Of course people are aware of superior brands, but these days, they just come to me with ₹10 and ask for a product that will provide maximum quantity and value for the price,” says Singh.

“Aaj kal gaon mein toh daily kamaana, aur daily khaana,” he explains, referring to how most people—especially daily wage-earners and marginal farmers— are buying small units on a day-to-day basis. So high-value tubes of face creams are being sidelined for smaller packs, while shampoos and hair oils are only being bought in one-time-use sachets priced at ₹1 or ₹2. Soaps are being sold as usual, he claims, but “that is a product with the lowest margins”.

Singh, who is married with three daughters and one son, complains that customers are also taking longer to repay credit. This means he may delay paying his sub-stockists, who in turn face pressure from super-stockists and FMCG companies. With credit channels drying up, customers become more cautious about their purchases.

“The margins are already low for small retailers like us, and when people reduce or stop buying, it becomes more difficult. This business virtually has no benefit,” says Singh, who refuses to divulge his revenue, but claims that it has fallen by almost 40 percent over the last year.While demonetisation in 2016 and the Goods and Service Taxes (GST) in 2017 created a cash crunch that crippled rural India, other factors like stagnant rural wage growth, crop failures, monsoon irregularities and drop in area under cultivation have negatively impacted consumer spending. Macroeconomic conditions like limited beneficiaries to the PM-Kisan Scheme, lower government spending, lower procurement despite increase in minimum support prices (MSP) have also impacted FMCG consumption.

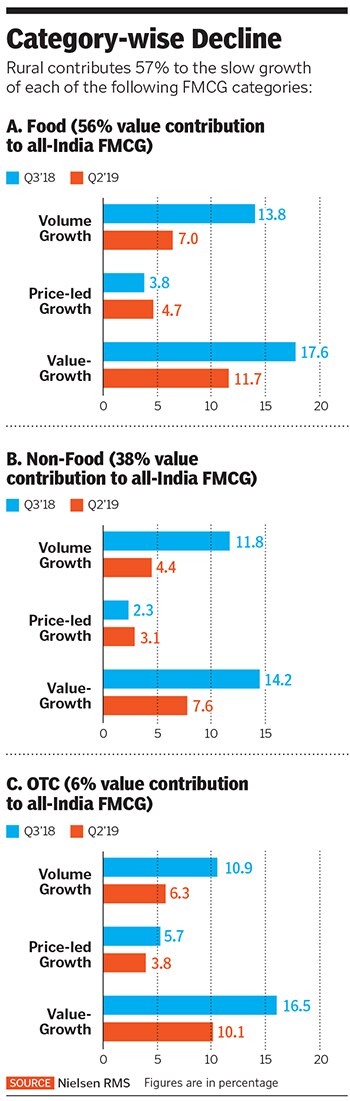

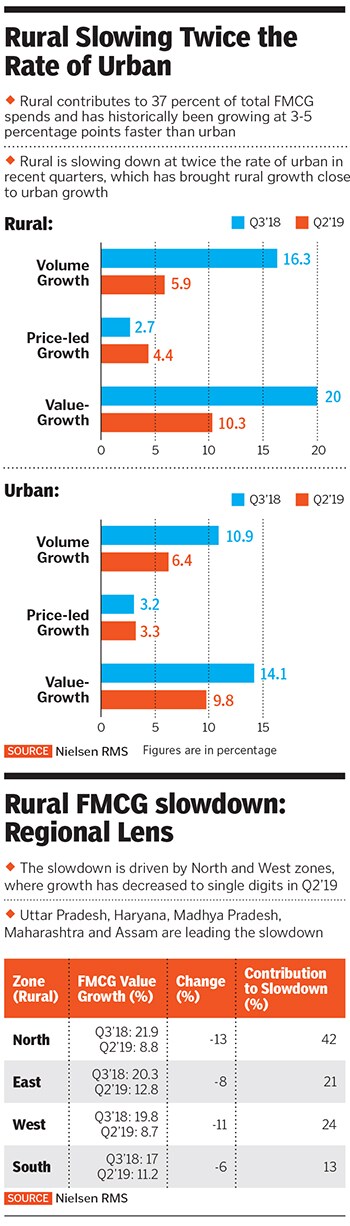

“The [FMCG] slowdown is more pronounced in rural markets, on the back of consumption—and this is directly linked to rural wages,” Sunil Khiani, retail measurement services lead, Nielsen South Asia tells Forbes India in an email. In July, the market researcher had lowered its 2019 growth outlook for the FMCG sector to 9-10 percent, down from its previous forecast of 11-12 percent.

Demonetisation and GST particularly hit the informal sector—leading to business failures, plant closures and job losses. According to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CIME), the unemployment rate in July 2017 (when the GST was introduced) was 3.4 percent and had reached over 9 percent at the end of August 2019. The liquidity crisis faced by Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFCs) has also had a ripple effect on the FMCG sector, while Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth rate in the April-June quarter was 5 percent, the lowest quarterly GDP growth rate in six years.

“At the beginning of the year, we saw softening driven by essential and impulse food categories however, this quarter [ended June 30, 2019] has witnessed slowdown across all food as well as non-food categories, with salty snacks, biscuits, spices, toilet soaps and packaged teas leading the slowdown,” says the Nielsen report. Harsh Goyal, a super-stockist of FMCG products, deals with 120 retailers across 30 villages around Gulaothi city in Uttar Pradesh. His annual revenue has dropped by 40 percent

Harsh Goyal, a super-stockist of FMCG products, deals with 120 retailers across 30 villages around Gulaothi city in Uttar Pradesh. His annual revenue has dropped by 40 percent

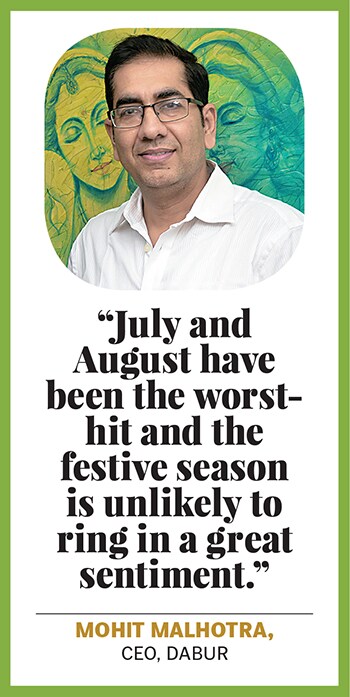

Image: Amit Verma[br]Companies admit that the shoe has started to pinch as consumption has been cooling for three straight quarters. “July and August have been the worst-hit compared to the previous quarter and the festive season is unlikely to ring in a great [consumer] sentiment,” says Mohit Malhotra, CEO, Dabur. “The slowdown seems to go from bad to worse month-on-month… it’s likely that we might not see any kind of assuaging till the next couple of quarters, also given that government announcements have not been transmitted on-ground.” Nearly 45 percent of the Ghaziabad-headquartered company’s business comes from rural markets.Srinivas Phatak, chief financial officer, Hindustan Unilever (HUL), says that while rural markets historically grew at about 1.5 times urban, more recently rural growth is close to or at par with urban growth. He says that market growth has moderated, even as the company “posted 7 percent revenue growth in the first quarter and 5 percent volume growth, which is a healthy growth in an FMCG context”. Expanding distribution and credit

Expanding distribution and credit

While retailers in rural areas are suffering due to low consumer demand, stockists have problems of their own. Harsh Goyal, a super-stockist of FMCG products, sells products of companies like Marico, Emami, Patanjali, Himalaya and Dabur. His company Riya Enterprises deals with 120 retailers across 30 villages around the Gulaothi city in Uttar Pradesh.

Goyal’s annual revenue of around ₹4 crore, he says, has dropped by 40 percent. “Retailers are buying less. For example, Patanjali’s annual sale value, which was around ₹7 to ₹8 lakh, has dropped to ₹4-5 lakh now. Sales of Nihar Shanti Amla hair oil and Saffola Gold oil, our bestselling items from Marico, have also reduced from ₹5 lakh annually to approximately ₹3 lakh,” he says, adding that the levy of 2 percent TDS on cash withdrawals beyond ₹1 crore (implemented September 1 this year) has also hit the trade hard. “Our business is mostly cash-based and we deal in lakhs of rupees every day. We will withdraw over ₹1 crore in a week’s time, and if we end up paying TDS on this, the costs will obviously become higher and impact the supply chain.”

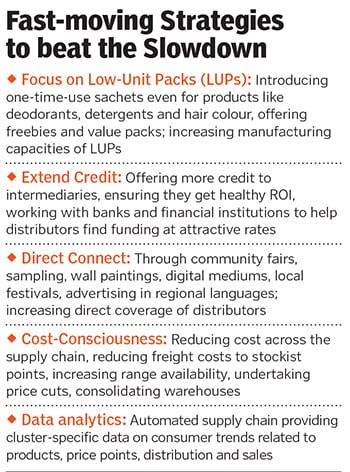

FMCG companies are trying to address some of these concerns and adapt to the slowdown by working more closely with their distributor partners. Malhotra of Dabur says the organisation is willing to extend more credit to their intermediaries, while encouraging cost consciousness across the value chain. The company is working to reduce freight costs to stockist points, and is increasing the range availability at stockists. It is also pressing the pedal on low price-point innovations by augmenting the manufacturing capacities of low-unit packs (LUPs) across tax-free havens like Pantnagar, Baddi and Tezpur.

“LUPs might seem like margin-dilutive propositions compared to larger packs, but it gets compensated by modern trade and ecommerce where you sell larger packs. The average selling price of larger packs is ₹200-₹300, while LUPs are at a ₹1 price point. If you make a 60 percent gross margin in the former, there is a 20 percent gross margin in the latter,” explains Malhotra, who is creating product portfolios specifically for modern trade.

As per BSE filings, Dabur’s consolidated margins were at 19.72 percent in the quarter ended June ’19, up from 18.67 percent in the same quarter last year. “Ecommerce growth is pulling up the momentum lost in general trade, more or less. Our ecommerce growth is about 50 percent, but it only contributes to about two percent of the business. While this hardly compensates for the 40-50 percent of general trade slowdown, it is a silver lining,” Malhotra says.

Phatak of HUL says their direct distribution model helps them place the right product and assortment on retailers’ shelves to meet differentiated consumer needs. “We have a strong relationship with our distributors and make sure they get a healthy ROI. In parts of central India, where we have been trying to build distribution scale and size, we are trying to work with banks and financial institutions to see how we can help partners find funding at attractive rates.” HUL’s strategies, Phatak says, revolve around the idea of a “disaggregated India”, where the country is divided into 14 clusters, each having a separate plan depending on the demographics, income and wage levels of the area.

“We want to invest in the capabilities of our 120,000 Shakti ammas [of Project Shakti, which empowers rural women to create livelihood opportunities] so that this channel works for us all the time, specifically should there be a slowdown or moderation,” he says. “We are establishing a direct connect customised to the needs of many Indias and mini Indias, where we leverage community fairs, sampling, wall paintings, digital mediums and local festivals to connect with people.”

Last month, HUL’s Lux and Lifebuoy soap portfolio took a price cut of between 4 and 6 percent. According to research firm Euromonitor, these are the two highest-selling brands in India’s ₹20,960 crore toilet soap market. Phatak says these cuts were not a response to weak demand, but passing on benefits of cheaper inputs like palm to the consumers.

“We have a price-product portfolio that is amenable to all segments. So I do not believe people will fall out of the consumption basket [because of a slowdown], they will just find the right fit for their liquidity level. So how you play with your portfolio becomes important and this will continue irrespective of economic cycles,” he says. HUL’s consolidated margins were at 24.86 percent in the quarter ended June 30, 2019, up from 23.26 percent in the same quarter the previous year, as per BSE filings.

Volume and Visibility

Companies agree that increasing competitive intensity across markets, segments and categories, and bearish commodity prices, calls for more investments in promotions and product innovations.

Chennai-based CavinKare is credited with pioneering the shampoo-in-a-sachet, an innovation that has resulted in sachets accounting for 89 percent of all shampoos sold in India today. It is now applying the same concept to other emerging personal care products like deodorants and hair colours. The ₹1,600-plus-crore company is conducting pilot launches of 2 ml, one-time use sachets for perfume under its Spinz brand, priced at ₹3. Similarly, it has launched its Indica hair colour in a sachet format, and an anti-dandruff shampoo under its Meera brand in the South.

CavinKare Chairman CK Ranganathan says they are trying to minimise the impact of the slowdown by “improving the quality of our own reach”. This involves, he explains, creating a separate vertical for rural markets, which will focus on understanding the behaviour of rural consumers, adoption challenges etc. to leverage opportunities. The company, which is currently present in around 8 lakh outlets across the country, is aiming at a million outlets by 2021.

“Our entire supply chain is going digital, starting from the way we pick orders in rural areas to how they are serviced. This back-end automation creates a structured information flow right across the value chain, including salesmen and distributors. Our analytics wing will use this data to give us consumer trends in specific clusters, with products and price points that are working there,” says Venkatesh Vijayaraghavan, CEO—personal care and alliances, CavinKare. “Right now, a large part of our rural reach is indirect through sub-distribution, but this approach will help us reach the bigger villages directly and strengthen indirect coverage in the smaller neighbouring regions.”Rural marketing expert Pradeep Kashyap, founder of MART Global Management Solutions LLP, says that the rural wage increase has been squeezed due to low budgetary allocations to the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) in the last five years. In some cases, he adds, the allocated funds haven’t reached the states. On the other hand, farmers are not getting proper realisation for their produce due to inadequate storage systems and marketing support.

“Despite this, it would help if companies keep their promotional communication on, because in rural areas, there is something called brand stickiness. People might downtrade and expect superior value out of their brands, but might not switch that easily. So special deals, value packs and promotions will work well for FMCG companies during a slowdown,” he says.

Sunil Kataria, CEO, India and Saarc, Godrej Consumer Products Ltd (GCPL), agrees with Kashyap and says that the wallet of the consumer is getting divided among other emerging necessities like telecom, fashion and entertainment, and it is up to marketeers to create their own shares.

“One thing we have learnt from previous slowdowns is that consumers pull back. They either downtrade in essentials or postpone purchases. Consumer sentiment is negative, so this is the time when companies should focus on volumes,” he says. As per BSE filings, GCPL’s consolidated margins show a marginal increase of 15.81 percent in the quarter ended June ’19, up from 15.36 percent in the same quarter last year.

The rural market constitutes about 31 percent of total sales for the maker of Cinthol soaps and Hit insecticides, which faces competition from regional and informal sectors. The company’s major strategy involves micro-marketing to the smallest of clusters. For example, the company rolled out Urdu advertisements of their Godrej No. 1 soap for the Muslim-dominated region of Rohilkhand in Uttar Pradesh, Bhojpuri films in the Bhojpur district of Bihar for their Nupur hair colour, and are using the local Dakhni language in their communications to stimulate demand in Maharashtra’s Marathwada region.

Companies unanimously believe that the big-bang reforms stimuli promised by the government will soon script a turnaround. Till then, says Harsha V Agarwal, director of Kolkata-based Emami Limited, companies must bank on strong stock-keeping unit (SKU) strategies. The manufacturer of Navratna hair oil, Boroplus cream and Zandu balm believes that region-specific SKUs across product categories through direct distribution would help them stay ahead of the curve. “Companies need to work harder and more smartly to come out stronger. Money has to be spent smartly and in the right places,” says Agarwal.

Abneesh Roy, executive vice president, Edelweiss Securities, says that strategies like price cuts, focus on LUPs and strengthening of direct distribution indicate that companies are acting quickly based on the experiences of past slowdowns. “There is a risk of the slowdown continuing if government announcements are not followed by implementation, but I would not expect a let-down on that front. We could expect rural recovery by the end of this fiscal year.”

First Published: Sep 18, 2019, 13:59

Subscribe Now