Despite Slowdown, Aspirations Propel Luxe in India

India is one of the last untouched markets for the luxury goods industry where the novelty and social relevance of big-ticket brands continue to drive growth

India has hardly been a stranger to luxury. History can recount several tales about the country’s proclivity towards the opulent. Till a couple of decades ago, that narrative would revolve around only its royalty: The maharajas and, later, the corporate and industrialist rajas.

For instance, in the 1930s, India famously accounted for a fifth of all Rolls Royce cars sold worldwide. The maharajas, in particular, made a beeline, and some with rather eccentric motives. It is even said that Maharaja Bhupinder Singh of Patiala, on a visit to London, was seemingly insulted by the British makers’ refusal to accept his order. He promptly bought a consignment of three cars and converted them into garbage trucks.

In the 2000s, though, there is a new world order. Big-ticket, whimsical spending is no longer the bastion of a few. It is enveloping newer geographic regions and making maharajas out of the middle-class—although it is unlikely that you will see a Rolls Royce trash can in your neighbourhood.

While we continue to covet international luxury brands, they are now equally chasing us. The country is one of the last untouched markets for high-end goods, still leagues behind peers China, Brazil and Russia on penetration.

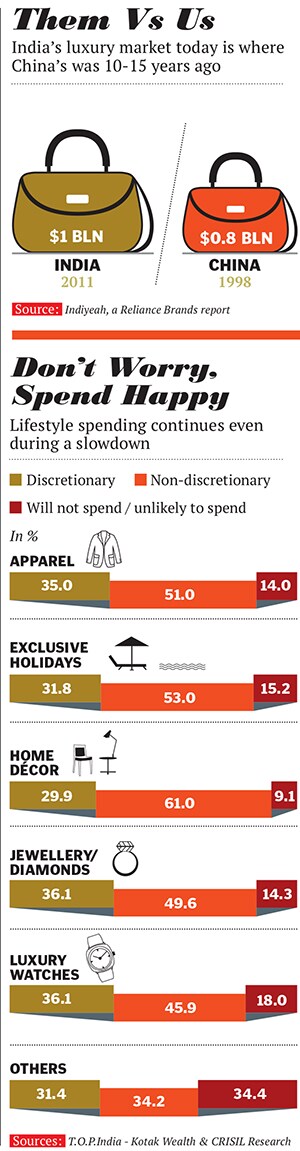

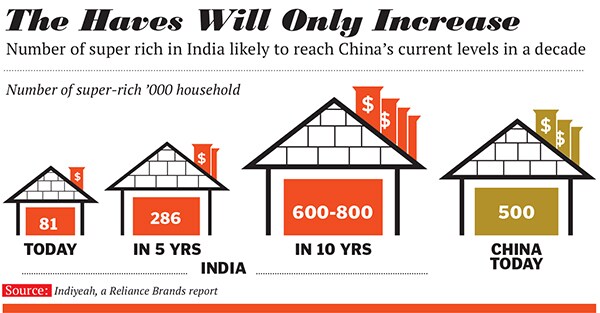

Commentators talk of untold riches once the market finally reaches an inflection point. “The luxury market in India is at least a decade behind China but it is getting there. Even with slowing economic growth, we should get to a critical mass by the end of the decade,” says Sanjay Kapoor, managing director of Genesis Luxury, a retail company that has brought labels like Gucci and Canali to India. For now, the brands are happy to seed the market and wait for the tipping point to come.

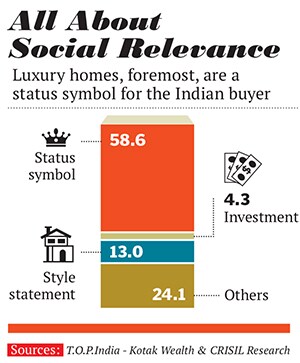

It is inevitable that it will. For India’s large aspiring middle class, the luxury business makes a bold promise: There’s that bespoke shoe that puts you a touch above the rest. The weekend home with a private swimming pool inspires a touch of awe. The custom-made wood-panelled Maybach flown in from Germany becomes a talking point at soirees.

This social relevance drives luxury buying and makes consumers loath to slow down purchases. Not that our market is large enough to be significantly influenced by recessionary trends: Bain and Co, in its luxury report for 2012, estimates it at $6 billion, with cars and personal goods accounting for $1.5 billion. Compare this to $75 billion for the US, $20 billion for China and $4 billion for Brazil.

Besides, the novelty value is incalculable as a majority of new buyers are still making their first purchase. Also, unlike in the West, Indian (and Chinese) luxury buyers like to flaunt their acquisitions. Consider this foreign diplomat’s wife’s surprise at witnessing a bunch of women comparing bags at a society party. “Here it seems you buy things for others,” she says.

The Big-Ticket Opportunity

The building blocks of India’s luxury industrial complex were laid in the last decade. Retail started moving beyond five-star hotels to high-end malls. There are now over 60 luxury outlets in the country, the Bain report says.

Euromonitor estimates that the number of HNIs (high networth individuals) with over $1 million in liquid assets has almost trebled to 46,000 during 2006-2013. In the same period, the wealthy and affluent with disposable income of more than $100,000 (Rs 60 lakh) rose to 1.1 million from 600,000. Premium alcohol imports rose by 52 percent in 2012—a year in which India added seven new billionaires, taking its total to 55, according to the Forbes billionaires list. Luxury car sales rose at a compounded rate of 40 percent between 2008 and 2012, as per the Bain research. This avalanche of figures underscores the potential but does not factor in the hindrances to the anticipated boom.

First, the lack of quality retail space in India: There are only three malls that can be broadly classified as luxury—DLF Emporio (Delhi), Palladium (Mumbai, technically a mixed-use mall) and UB City (Bangalore). Nine new ‘luxury destinations’ are in the works and should open by 2016, according to Indiyeah, an in-house publication by Reliance Brands.Second, India is meandering on the same path as China where luxury brands had to grind through a decade of slow growth before take-off. The point at which India’s growth graph represents a hockey stick curve could be as much as a decade away.

Forbes India’s interviews with multiple industry watchers indicate that, notwithstanding the occasional roadblock, the expectation is that growth will be secular and strong. The Indian buyer has evolved over the last five years. And retailers, too, have the ‘one size fits all’ approach.

The Indian Buyer

“There are those that have been born and brought up in the lap of luxury. This is the traditional luxury consuming class,” says Abhay Gupta of Luxury Connect, a boutique consultancy. This set is diverse, including land owners, industrialists, the film industry as well as politicians by dynasty. They have traditionally shopped abroad. The latest trends are foremost on their minds, value for money is a secondary consideration. “They don’t need to be sold luxury,” says Darshan Mehta, CEO, Reliance Brands.

Next in the pecking order is the returning NRI professional used to shopping abroad. “This segment, being financially savvy, doesn’t hesitate to compare prices with those overseas and will walk away if they are higher by more than 5-10 percent,” says Gupta. At present, they comprise the largest chunk of spenders in India but, in time, are likely to be eclipsed by the third type of luxury buyer.

Meet the new moneyed class created by soaring land prices in India. These consumers have sold their land holdings and are not afraid to spend: Cars, electronics and fashion are on their shopping list. “This is the type of buyer that needs to be dealt with most carefully,” says Mehta. Cars are the most conspicuous consumption–often the first major purchase after land is sold. Fashion is a close second on the spending meter. These cash-only purchases take place through word-of-mouth and brands have had to train their staff in the art of not instantly profiling such customers. “You need to speak to them in their language and make them feel comfortable,” says Kapoor. They don’t want this set intimidated and taking their business to a competitor. For them, bling is in and the understated is out.

Finally, there are the bargain hunters who come out in hordes during end-of-season sales. Brands seem to have a love-hate relationship with them as such bulk buying may distort their painstakingly-built upscale positioning. Their shopping bags are prominently marked ‘sale’ or ‘half-price’. Not surprisingly, this class of buyer has been hit hardest by the recent slowdown.

China in front, Again

The consumer base may have widened and diversified but Radha Chadha, an independent luxury commentator and author of The Cult Of The Luxury Brand, says that the “democratisation of luxury spending” has not yet taken place in India. She cites South East Asia as an example, where even secretaries have at least one luxury item in their wardrobe. You can verify this by travelling in Singapore’s metro system where assistants are seen toting Louis Vuittons and Pradas. “In these markets, the rich account for a small percentage of spends while the middle class constitute a much larger proportion,” she says. The income levels in India may be lower, but it is also a mindset issue.

China started its tryst with big-ticket labels in 1991 when Louis Vuitton and Ermenegildo Zegna entered the country. They, too, faced teething issues. There was the obvious lack of retail space. Initially, they clustered around five-star hotels in Shanghai till Plaza 66, a luxury mall, opened. The brands had to really work the market and stay content with a steady 15-20 percent growth. The inflection point only came in the 2000s when sales increased dramatically, at times even doubling or tripling in a year.

This will evoke a sense of déjà vu for the Indian luxury retailer. It is only logical that the industry anticipates a similar boom by 2020.

There has been a pause in the Chinese surge, of late, and Mehta‘s analysis of this hiccup is intriguing. He says growth there was fuelled by two factors. One: ‘Gifting’, a euphemism for corruption. Two: The ‘second wife’ or mistress for whom luxury goods are bought. The crackdown on gifting has resulted in the slowing. Neither reason is prominently (or openly) utilised for luxury buying in India.

Slowdown and Changes

At $1.5 billion, fashion contributes to a bulk of luxury spending in India property comes a close second. Lodha, Oberoi Realty and Omkar have launched homes in the Rs 30-50 crore price bracket. Buildings in Mumbai’s Lower Parel and Worli areas are the ideal example where buyers are usually approached discreetly and sales take over a quarter to close.  According to the Top of the Pyramid report prepared by Kotak Wealth and Crisil Research, 14.7 percent of luxury real estate buyers have made their money in the real estate business. For them, location and exclusivity of the project is critical.

According to the Top of the Pyramid report prepared by Kotak Wealth and Crisil Research, 14.7 percent of luxury real estate buyers have made their money in the real estate business. For them, location and exclusivity of the project is critical.

“One prospective buyer wanted to know if the service lifts could carry the huge glass panels used in the windows as a single piece. Another wanted to know if the buildings were earthquake proof,” says Babulal Verma, managing director, Omkar. They were curious about the quality of the architects. In fact, 53 percent of luxury buyers will go for a project only if it has a renowned architect, according to the Kotak-Crisil survey.

A slowing real estate market has so far not impacted sales in this segment. Buyers are more concerned about a depreciating rupee and a lacklustre stock market. The home is considered a once-in-a-lifetime purchase and a preferred investment they would rather hold off on upgrading to a luxury sedan. “And where will I drive a Rs 3-crore car in Mumbai?” says an industrialist buyer, 32, already the owner of a Jaguar.

This resonates with Chadha’s view that “when growth slows, people start spending on items that are likely to retain their value over a longer period of time”. So, out goes the car, but the luxury watch is still bought.

In the short term, a depreciated rupee is likely to cause the biggest headache for retailers and buyers alike. Chadha says that the recent rupee depreciation can result in growth projections being wound down—brands expect to revise prices before the festive season. Kapoor says he has seen a slowdown in sales in August. “Rich people who have taken a blow to their paper wealth are now less sure of spending,” he says.

But the larger-than-life story of consumerism is unlikely to get derailed. Brands have reported a steady 15-25 percent growth.

Plus, the penetration of luxury consumption is still low enough for the trajectory to continue north, only the pace may reflect the larger sentiment.

Meanwhile, expect the Indian consumer to get even more discerning. The example was set back in the 1930s by the Maharaja of Patiala. A few years after the garbage truck incident, the Maharaja of Bharatpur had a problem getting Rolls Royce to service his cars. His solution too was to turn the cars into garbage trucks. The company wasn’t taking any chances: They quickly sent a team of mechanics to service them.

First Published: Oct 14, 2013, 06:51

Subscribe Now