Jay Galla, the driving force behind Amara Raja Batteries

Jay Galla, vice chairman & managing director of Amara Raja Batteries, also wears a political hat, but never at the expense of the company which has challenged the might of Exide

As the black Mercedes-AMG G 63 off-roader hits the dirt track leading to a 45-acre construction site at Velagapudi village in Andhra Pradesh, hundreds of construction workers taking a bath in front of a large, open, surface-level water tank turn around to see who the early morning visitor is. It is 8 am on a mid-April morning and the SUV screeches to a halt near an elevated platform in the middle of the site which is 16 kilometres from Vijayawada town and part of Amaravati—the new capital region that is being built by the Andhra Pradesh government.

Jayadev (Jay) Galla, vice chairman and managing director (MD) of Amara Raja Batteries (ARB), emerges from the vehicle to inspect the progress of the ‘interim government complex’. “After completion in June, these buildings will house over 12 lakh employees of the state government,” he says, pointing to the multiple structures that are currently pillars and pre-fabricated beams. A permanent government complex is coming up on the banks of Krishna river farther away which will be ready by 2018. There is a palpable rush to build this complex. Reason: “The sooner we shift from Hyderabad (the capital Andhra Pradesh shares with Telangana), the better for our state’s economy. By being in Hyderabad, we are contributing to Telangana’s economy,” says Galla.

As a member of the crucial Capital Planning Committee, Galla’s involvement becomes even more understandable. “The chief minister [Chandrababu Naidu] wants to make Amaravati the most liveable city in the world, similar to Vancouver (Canada) or Copenhagen (Denmark),” he says, and Naidu chose him to help realise this dream. Not just for political factors (Galla is Telugu Desam Party’s Lok Sabha member from the Guntur parliamentary constituency which forms part of Amaravati) but also for his business acumen.

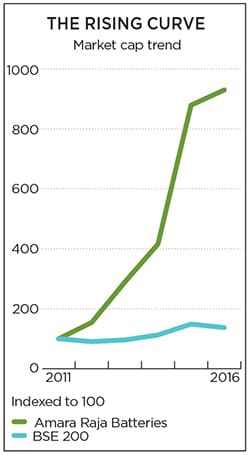

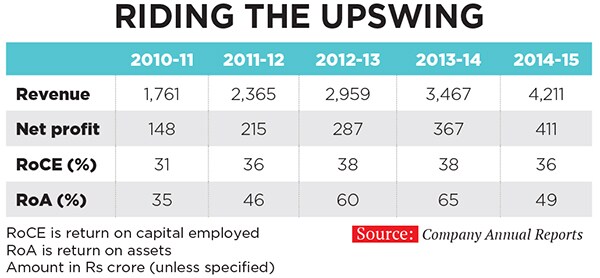

Consider that ARB, under Galla’s watch, has become a market leader in the industrial battery segment and is within kissing distance of the top spot in the automotive space as well (where Exide Industries currently leads). The company is also a technology leader, having introduced valve-regulated lead-acid (VRLA) and maintenance-free batteries in the country (the three-tier air-conditioned coaches in Indian Railways, company officials claim, would not have become a reality in 1993 but for ARB’s innovative batteries). As a result, its turnover and profits have grown strongly. ARB’s market cap has risen from Rs 1,615 crore on March 31, 2011, to Rs 15,023 crore on March 31, 2016, at a CAGR of 56 percent. Simply put: An investment of Rs 100 in 2011 is worth Rs 1,000 now.

All of this was facilitated by some critical decisions taken by Galla, including the company’s foray into the automotive battery segment. Entering the Automotive Segment

Entering the Automotive Segment

This was not an easy call. “It took me five years to convince my father,” says Galla. Ramachandra N Galla, founder and chairman of the Amara Raja Group, had his reasons. “An automotive battery foray would mean a shift in focus from B2B to B2C and this would call for expertise in branding and distribution which we did not possess,” Galla senior, who set up ARB in the early 1990s, tells Forbes India over the phone from Hyderabad. That apart, the industrial battery segment was garnering the company a substantial profit of Rs 60 crore on a Rs 180 crore turnover. Also, no company till then had succeeded in taking on Exide, which had become a generic brand in the auto segment, with a strong mindshare as well as market share.

“The chairman saw it [the automotive foray] as an extraordinary flirtation,” says Ramana Prasad Alam, CEO of group company Amara Raja Electronics. But Galla was convinced that significant growth and leadership was not possible without a strong presence in the auto space. Global auto majors like Ford, Hyundai and others were entering India at that time and, more importantly, Exide was entering the VRLA segment pioneered by ARB in the country. “If Exide chose to attack us by dropping the price of VRLA batteries, we had no way to retaliate,” says Galla.

He convinced his father in 1998 and Amaron batteries were launched in 2000. It took the company five years to use up the first million battery capacity it had set up. That took a toll on the 2003-04 and 2004-05 results. “People started seeing me as incompetent,” says the 50-year-old Galla who took over as MD in 2004. That, however, changed—today automotive batteries account for 55 percent of the company’s revenues (and profits). Its market share of 25 percent is just 5 percentage points lower than Exide’s.

Partnership with Johnson Controls

Once the decision was made to enter the automotive battery space, the next call to be taken was on the partner. The automotive battery manufacturers in India till then preferred Japanese technology (Standard had it from Furukawa and Amco from Yuasa) which offered dry-charged batteries (batteries would come dry from the factory and dealers added acid and charged them). Conventional wisdom said ARB should also go the same way. But Galla decided on American company Johnson Controls which did not even make batteries in the size India used. “But they are technology leaders,” he says.

The batteries designed and launched in India (jointly with the US partner) were five generations ahead. They came factory-charged and required zero lifetime maintenance (traditional batteries required periodic topping up of distilled water): These proved to be key differentiators. Unlike Japanese companies, Johnson Controls, which has a 26 percent stake in ARB, was also open to sharing the technology. “Even today we have one board meeting every year at a place where Johnson Controls’ plant is located to learn about their best practices,” says SV Raghavendra, Group CFO.

That said, ARB too has its own share of best practices.

Adding Capacity at the Right Time

For instance, it has mastered the art of adding the right capacity at the right time without over-investing. Despite large-scale investments (the company spent Rs 1,800 crore in the last four years), it has avoided the trap of unutilised capacity by following a five-year strategic planning process. It enables the company to study the market and plan capacity addition early. ARB adopts a modular capacity expansion process where the front-end and back-end infrastructure is set for full capacity and the assembly lines are added based on demand. The creation of UPS battery capacity is a case in point. The company identified the emerging demand for data centres by the turn of the century and was ready with the capacity when the market exploded. It is the market leader in that space and has built the single largest UPS battery manufacturing facility in the world at Chittoor in Andhra Pradesh.

Treading a Different Path

Galla opted to do many things differently. “He changed the way automotive batteries were made [factory-charged], sold [in air-conditioned shops on a cash and carry basis] and serviced [36-month warranty] in the country,” says Rajesh Jindal, chief marketing officer of the company’s automotive strategic business unit. Automotive batteries were never advertised (it was considered a low-involvement category) but Galla launched a branding blitzkrieg to promote the Amaron brand (recall the very first claymation ads used in the country that introduced the brand and its technical superiority). These strategies helped the company take on Exide effectively. “Amara Raja Batteries is gaining at the expense of Exide,” says Sanjeev Bhasin, EVP-markets at brokerage firm IIFL.

Eye on Profits

While Galla is focussed on market leadership, growth was never at the cost of profits. For instance, tapping original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) in the automotive space was a sure-shot way to increase volumes. But it comes at a cost. “The prices they offer are low and at times, a little more than the marginal cost of production. The replacement market on the other hand offered handsome margins,” says Jindal. For a newcomer with a million unit capacity on the ground, it was a reasonable option to go for the OEMs but Galla decided on an alternative route: He would limit the OEM share at one-third of the total automotive capacity.

In another situation, in the industrial battery space, a large telecom player dropped its procurement prices sharply. “To our shock, sales to the company, our biggest buyer, were stopped,” says Srinivas Ganga, chief marketing officer, Industrial Strategic Business Unit. These actions explain the 20 percent operating margin the company enjoys compared to Exide’s 17 percent. They also highlight Galla’s approach, a balance of boldness and pragmatism, which also manifests in his other foray—politics.

The Politics Call

The seeds of becoming a politician were sown early in Galla’s life, when he saw his maternal grandfather P Rajagopal Naidu, a freedom fighter, serve the public both as a Parliamentarian and otherwise. “Through business, you impact a few thousand families, but if you can influence policy, a lot more people can benefit,” says Galla.

Having set his mind on politics, he ensured he had a leadership team he could count on. He identified the right talent and empowered them, also putting them through a leadership development course at IIM-Bangalore. “We have two apex leadership structures—the Growth Council (Grocon) for operational decisions and the Amara Raja Corporate Council for strategic decisions such as acquisition, divestment, etc,” says Jaikrishna B, president-group HR. These layers of leadership also prepare the company for the future.

Future Ready

“One of the biggest regrets I have is that ARB does not have an overseas manufacturing facility. We were growing at over 30 percent year on year and did not have the appetite to look beyond India. In hindsight, we should have,” he says. He is changing gears now. A group strategy office has been set up to explore such opportunities.

“That we are a zero debt company with a cash war chest of Rs 300 crore gives us immense scope to leverage and fund acquisitions,” says Raghavendra. Dividend payout has been capped at 15 percent of PAT to conserve resources. Galla has set an ambitious target of $10 billion revenue for the group by 2025 (ARB and associate companies currently aggregate a shade under $1 billion in revenues).

“We cannot achieve this target if we continue to confine ourselves to India and just grow organically,” he tells Forbes India at his home in Guntur, which doubles up as his political office, before driving away in a convoy of cars to distribute land pattas (titles) to poor people.

First Published: May 24, 2016, 07:29

Subscribe Now