Nine to nine: How we can reclaim 9% growth

Why getting back to record levels of economic growth hit a decade ago will be no walk in the park

Foreign investors are buying commercial property due to the attractive rental yields

Foreign investors are buying commercial property due to the attractive rental yields

Image: Getty Images

If you’ve been a diligent reader of business newspapers, spent time watching business anchors on television and ardently followed policy pronouncements by the government, chances are you’d fall in the camp that believes a spurt in India’s growth is just a matter of time.

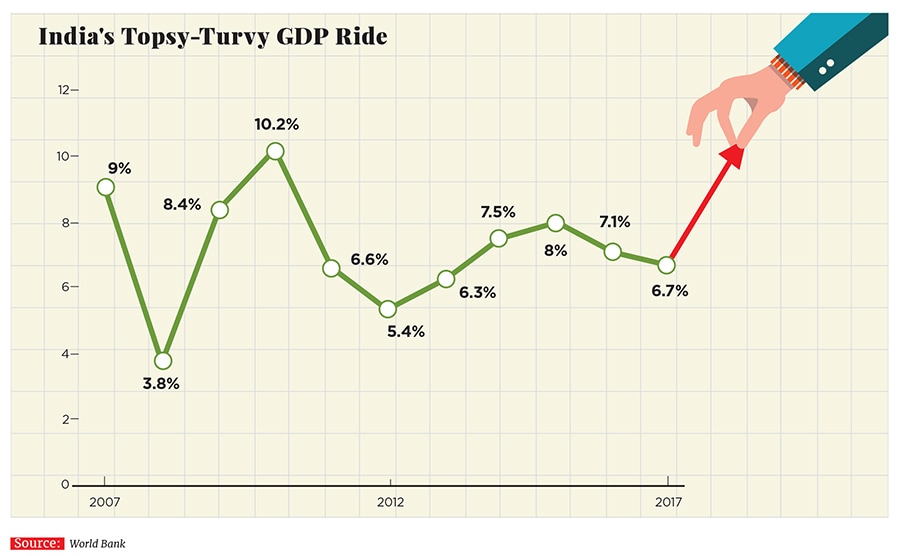

After all, the popular narrative (and consensus) has been to suggest that once the significant structural reforms initiated by the government begin to bear fruit, India would be in for rich pickings. In short: India is within sniffing distance of touching a rate of growth that exceeds 9 percent. The hope is that this time the rapid growth would rest on a firmer footing rather than a boom and bust cycle.

It was between 2005 and 2007 that India had three years of 9 percent growth. A decade after that growth spurt ended with the 2008 financial crisis is a good time to ask whether the Indian economy is primed for a higher growth trajectory. Forbes India spoke to a cross section of economists and people in industry to check if they’re as bullish about India’s prospects as the popular view. What emerged is that even while they agree that growth potential has moved up to 7-7.5 percent, they are cautious about the economy’s chances to exceed that in a meaningful manner. “A lot of impediments to growth have been removed but the political consensus required to get us to our growth potential doesn’t exist,” says RC Bhargava, chairman of Maruti Suzuki. “I believe that in the political battle that is going on we will certainly lose out on some growth,” he adds.The consensus pretty much is that India’s prospects remain tied to the global economy and that the country is vulnerable to external shocks such as higher oil prices.

This comes at a time when the perception of India rests on a firmer footing abroad. The last decade has seen a deepening of the story, what with the domestic economy being seen as the last significant economy with significant catch-up growth left. Companies salivate at the prospect of serving consumers with a per capita income of $3,500 and above, roughly twice of what it is today. They point to the Chinese domestic market, which blossomed once the country crossed $5 trillion output. So can India’s is the reasoning.

But first, here’s why it’s imperative to get to faster growth soon. India would be able to double the size of its economy every eight years —up from the current 10-12 years. And that would open the doors for creating 8 million jobs a year needed to keep the 18-24 year olds entering the labour force gainfully employed. Higher and faster growth would also help ensure India avoids the middle-income trap that has afflicted several major developing economies.  Investments & global factors

Investments & global factors

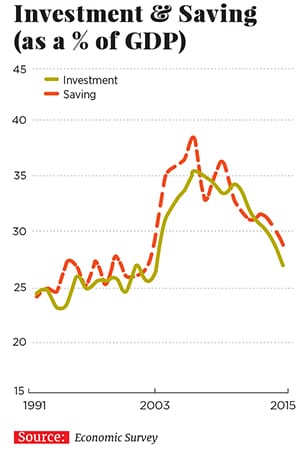

The seeds of India’s present investment drought were sown in the immediate aftermath of the Lehman crisis. As corporate India took that as a temporary demand shock and continued to add capacity, the investment rate recovered quickly. In hindsight that led to a massive build-up in surplus finance through huge leverage, which is still working its way through the system.

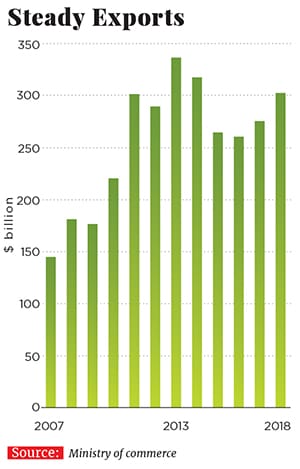

The growth in fixed investments has since plunged to a fifth (5 percent from 25 percent in the 2004-08 phase) and the government’s spending on infrastructure has been unable to fill the gap, leading to a sharp decline in India’s stock of capital, according to Nomura. As an example, Abheek Barua, chief economist at HDFC Bank, points to the fact that beyond the top three auto makers, companies are still making use of capacity that they had installed in 2011-12. Depending on the sector, this overcapacity will still take anywhere between three and five years to work its way through the system. Until then companies are wary of planning new investments.Further complicating the pitch has been the decline in global growth and trade growth at a time when the Indian growth has been increasingly correlated to global growth. “India’s growth correlation to global growth has moved up from 0.2 to 0.4 in the last decade. If global growth were to surprise by 1 percent, we’d get a 0.4 percent bump,” says Sachidanand Shukla, chief economist at Mahindra & Mahindra. As a result, another important driver of our growth—exports—has been largely flat for the last four financial years.  Demonetisation and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) meant that India hasn’t been able to take advantage of a modest increase in global growth since late 2016. GST has made it particularly hard for small exporters as refunds and credits remain stuck with the tax authorities, increasing their need for working capital and ultimately their cost of doing business. A stable rupee over the last four years has also resulted in some loss of competitiveness.

Demonetisation and the implementation of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) meant that India hasn’t been able to take advantage of a modest increase in global growth since late 2016. GST has made it particularly hard for small exporters as refunds and credits remain stuck with the tax authorities, increasing their need for working capital and ultimately their cost of doing business. A stable rupee over the last four years has also resulted in some loss of competitiveness.

For now, the only growth engine holding up is consumer spending and industry watchers are wary as to how much more this can add to growth.

Getting to 9 percent

So what could get India to that elusive 9 percent number and what would be the texture of that growth? What’s clear is that India lacks an important cushion that powered the east Asian miracle economies—global growth and the subsequent tailwind it brought about in the form of rapid export growth. “The global economy is different today than it was in the last 20 years. Countries that managed to grow rapidly did so in the backdrop of fast global growth,” says Sonal Varma, chief India economist at Nomura. “The contribution of global factors in helping a country reach its potential was a lot in the past and is not there now.”

The good news is that a lot has happened on the reforms front. Take, for instance, the formation of the monetary policy committee of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in 2016. For the first time, India has legislated that the RBI’s mandate is to target inflation within a band. This has the potential to eliminate the problem of growth volatility that bedevils developing economies, according to Shukla. It’s not uncommon to find developing economies overheating due to growth spurts, which are then accompanied by a rise in interest rates. This creates volatility in interest rates, currency exchange rates—something that foreign investors don’t take kindly to. The formalisation of an inflation target should help in considerably reducing that risk for India.

Inflation targeting is not something corporate India necessarily agrees with. “The lowering of our inflation rate has reduced the cost of debt while the cost of equity still remains high,” says Nikhil Sawhney, managing director at Triveni Turbines. As a result, entrepreneurs are wary of taking higher equity risk.

But, because of the stability, there are signs of the country attracting longer-term money. Foreign investors —from pension funds like CPPIB and CPDQ to sovereign wealth funds—have been on an asset-buying spree with commercial property being their preferred option due to the attractive rental yields. In time this could also include roads, bridges and warehouses. While it remains to be seen if these investments can stand the test of a rise in global interest rates, for now there is every possibility that they could provide a good supplement to the shorter-term stock market flows.GST has the potential to add between 50 and 100 basis points to growth. As do the government’s investments in rural India—where it wants to double farm incomes by 2022—and infrastructure, with an ₹850,000 crore investment for five years starting 2016 for the East and West dedicated freight corridors. The multiplier effects of these investments should again help add to growth. And lastly, at 27 percent, India’s women have the lowest participation in its labour force among all Bric nations. Even a small increase here could push growth up.

India’s biggest unknown remains the investment puzzle though there are some signs of a nascent pick up in demand. Triveni Turbines, a turbine manufacturer, is seeing a small uptick in orders. The company had seen demand for 0-100 MW turbines tumble from 4,500 MW during its peak to 750 MW last year. “Over the next five years, I see large drivers of demand—steel, cement, renewable energy generation contributing to an increase to about 3,000 MW a year,” says Sawhney. Industry sources point to JCB, which supplies road-making equipment as having its best year ever.

Small signs but when will private capacity expansion happen in a meaningful way? “We are still addressing the excesses of the previous cycle and till those are resolved it is difficult for the new drivers of growth to have a multiplier effect,” says Varma. To get to 9 percent she says investments have to rise to a run rate of 25 percent per annum from 5 percent today.

First Published: May 16, 2018, 12:10

Subscribe Now