Economic factors hold key to Modi's chances in 2019

Jobs, oil prices and rural economy will play a crucial role in determining Narendra Modi's fate in the 2019 elections

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur In a November 2013 speech, Narendra Modi had said: “If the BJP comes to power [in 2014], it will provide 1 crore jobs.” Jobs, and the hope of a better economic future, were key planks on which the BJP came to power.

Illustration: Chaitanya Dinesh Surpur In a November 2013 speech, Narendra Modi had said: “If the BJP comes to power [in 2014], it will provide 1 crore jobs.” Jobs, and the hope of a better economic future, were key planks on which the BJP came to power.

With the next Lok Sabha elections just a year away, it is important to analyse the economy, and how it will impact Modi’s chances. While the state of the overall Indian economy has been improving, the average Indian voter is concerned with basic things like jobs, food inflation, and fuel prices. Let’s look at these factors individually:

1) One million Indians are entering the workforce every month. Are there enough jobs for them? All is not well on this front. Here’s why:

a) The Indian Railways recently advertised for 90,000 vacancies and got 2.8 crore applications. This suggests that nearly 20 percent of India’s youth workforce looking for a job applied for these vacancies. Such instances of a large number of people applying for government jobs keep cropping up.

However, just because so many people apply for a government job, it does not mean that they are not employed. This is true, but only partly. India’s workforce is largely employed in the informal sector. It is estimated that more than two-thirds of the workforce is employed in the informal sector, which does not pay well.

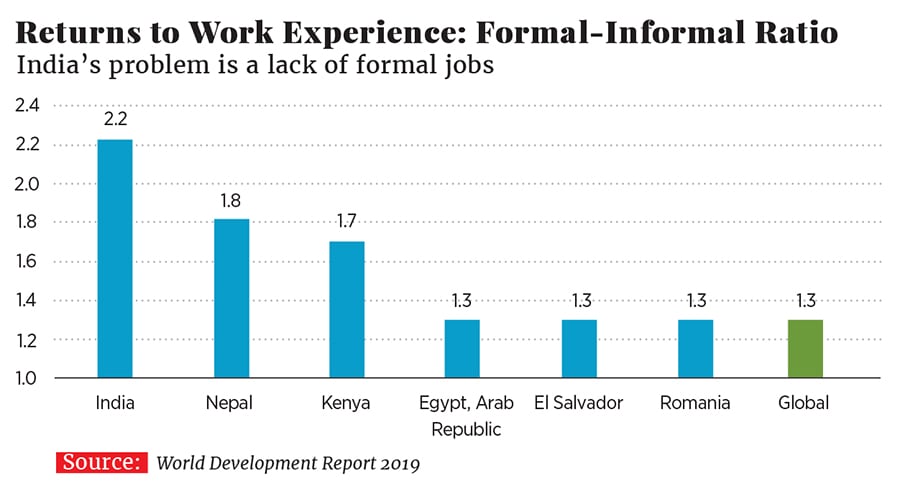

Also, India has huge underemployment and disguised unemployment. Four in 10 Indians looking for a job throughout the year aren’t able to find one. Agriculture contributes 39 percent of rural economic output, but employs 64 percent of the workforce, which means it employs more people than required. This explains why so many people apply for government jobs. India’s problem is a lack of formal jobs, and that continues (see chart).b) The government recently published Employees’ Provident Fund Organisation (EPFO) payroll data. It shows 3.11 million additions were made to EPFO across various age groups between September 2017 and February 2018. Niti Aayog Vice Chairman Rajiv Kumar extrapolated this to say that 6.22 million formal jobs were created in 2017-2018. But these conclusions are problematic.

First, companies start contributing to EPFO when the number of employees goes from 19 to 20. The addition of one job creates an illusion of 20 jobs in EPFO data. Second, EPFO had an amnesty scheme for defaulter firms, which has bumped up numbers. Third, if 6 million formal jobs were created in just one year, why are so many land-owning castes across the country demanding reservations in government jobs?

Fourth, if formal jobs have increased so rapidly, why isn’t it showing in the investments? As per the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), the total value of projects scrapped or dropped in 2017-2018 reached an all-time high. Completed projects dropped by 34 percent in value terms in 2017-2018.

CMIE estimates show employment rose by just 1.4 million people in 2017. In fact, employment opportunities for 15 to 24-year-olds fell by 7.22 million.

2) Through much of his regime, Modi has been lucky with low oil prices. The average price of the Indian basket of crude oil in 2015-2016 and 2016-2017 was $46.17 and $47.56 per barrel, respectively. It jumped to an average price of $56.4 per barrel in 2017-2018. The average price in April 2018 was $69.30 per barrel.

The government captured a significant portion of this fall in price by increasing the excise duty on petrol and diesel. The trouble is that petrol and diesel prices are now higher than in to May 2014, when Modi was sworn in as prime minister. This, despite the fact that oil prices are lower than what they were in 2014.

If oil prices remain high, and petrol and diesel prices too remain high, it can become a perception problem for the Modi government.

3) Another worrying factor is the fear of the government seizing money in public sector banks. This has emerged from demonetisation and the ill-timed Financial Resolution and Deposit Insurance Bill. The recent default by Nirav Modi has only added to this.

4) Agricultural growth in 2017-2018 is expected to be at 3 percent, against 6.3 percent in 2016-2017. Demonetisation is a major reason for this. Agricultural procurement was carried out primarily in cash and collapsed in the aftermath of demonetisation. The good news is that the India Meteorological Department has forecast a normal monsoon this year, at 97 percent of the 50-year average. So, this will be the third consecutive year of normal rains after the droughts in 2014 and 2015. The question is, will it translate into higher income for farmers.

5) One way of ensuring higher income for farmers is increasing the minimum support price (MSP) for crops. The trouble here is that an increase in MSP translates into food inflation, something that the Modi government has managed to keep a lid on.

From these explanations, it is clear that Modi is not well placed on the economic factors that matter to the average voter. In this scenario, it is possible that the government might do something along the lines of what the Manmohan Singh government did before the 2009 elections: Waive off farm loans.

One option for Modi is to waive off Mudra Loans, given that state governments are already waiving off farm loans. Between 2015-2016 and 2017-2018, around 12.3 crore Mudra Loans, amounting to ₹5,54,704 crore, were given.

Waiving off the entire amount will not be possible. But more than 90 percent of loans under Mudra are less than ₹50,000 the average loan is a little over ₹20,000. If half of this is waived off (i.e. ₹10,000), the total bill for the government would come to around ₹1,11,000 crore.

If UPA could waive off loans worth ₹70,000 crore around a decade ago, ₹111,000 crore can surely be waived off in 2018-2019.

The writer is the author of the Easy Money trilogy

First Published: May 17, 2018, 12:51

Subscribe Now