Bhakti Sharma: Turning the tide

The Mumbai-born-Udaipur-raised open water swimmer has swum in all five oceans of the world, sometimes with penguins and fin whales as cheerleaders

Bhakti Sharma

Age: 29

Open water swimmer

Bhakti Sharma was 16 when she surprised the lady at the immigration counter at London’s Heathrow Airport with her answer for ‘purpose of visit’. “I’m here to swim the English Channel,” she said with all honesty. “What are you here for, again? You must be crazy… it’s cold and long,” the lady shot back. Sharma merely smiled. Days later, in July 2006, she completed the 36-km solo swim from Shakespeare Beach in Dover, England, to Calais, France, in 13 hours and 55 minutes. Sharma conquered the English Channel again in 2008, with mother-cum-coach Leena and friend Priyanka Gehlot, becoming the first mother-daughter duo to accomplish the feat.

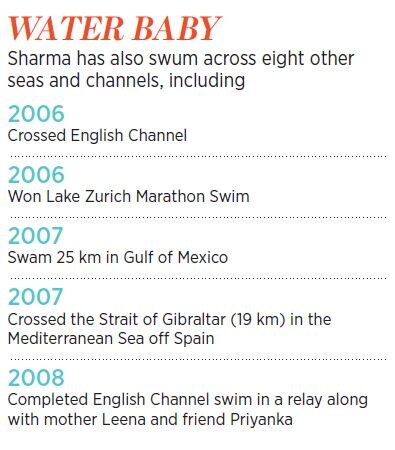

Water has been Sharma’s best friend since Leena pushed her into the deep end in a 12-metre swimming pool at the age of two. By 25, she had achieved the rare distinction of becoming the first Asian woman, and youngest in the world, to complete open swimming in the 1°C Antarctic waters, in a record time of 41.14 minutes (2.3 km). With it, she built an enviable résumé of having swum in all the five oceans in the world.Swimming has meant different things at different times for the Mumbai-born-Udaipur-raised girl, who also swam across eight other seas and channels. “Initially, it was a necessity because one should know how to swim to survive. When I began winning state and district championships, it turned into a competitive sport and it was all about proving myself. With open swims, it was about finding myself,” the 29-year-old says.

2019 W-Power Trailblazers list

In the absence of swimming pools in the desert city of Udaipur, Leena took an annual membership of Rs 5,000 with a private hotel and trained her daughter for an hour every day. While the amount was big nearly 25 years ago, it was the social and cultural battles that were harder to fight. A national-level swimmer herself, Leena would also get into the pool, despite taunts from relatives and locals who believed that women should cover their faces with ghoonghats (veils).

Leena, though, had spotted the spark in her daughter. “She was too good a swimmer and a quick learner. She picked up the butterfly, the most difficult of all strokes, in a day,” says the 53-year-old, who went from pillar to post to understand the requirements of taking her daughter to the oceans of the world.

Fluctuating weather, strong currents and non-linear paths are among the many challenges one encounters in the open sea. Besides, swimming is a lonely sport. But that’s where Sharma evolves as a person. “For long durations, it’s just you and the water… you and your thoughts. Rarely do people get to spend so much time with themselves,” says Sharma, who recently completed her masters in mass communications from the University of Florida and is pursuing her PhD there.

Sharma’s philosophical outlook aside, her sport also calls for fighting adverse situations alone. For instance, during her solo swim in the English Channel, she was stuck at one spot for about two hours. The fact that her parents were in a boat moving alongside was a big motivation. “I knew I had it in me and that I could struggle a bit more. Sometimes you want to do it not just for yourself but also for the people who made it possible,” says Sharma, a recipient of the Tenzing Norgay National Adventure Award (2012) from then president Pranab Mukherjee.

Premanand Gajinkar, 52, who coached Sharma at Mumbai’s Andheri Sports Complex for three months in a year for three years since she was 12, is not surprised by her ability to overcome challenges. “She had immense potential when she came to me. We built her endurance and strength with designated workouts. A swimmer must have power and confidence to deal with turning currents. Bhakti could easily combat such obstacles,” he says. “She practised for two hours in the mornings and two in the evenings, but never complained. She enjoyed those sessions.”

For her Antarctic sojourn, Sharma had trained for nearly two months in tough conditions. She quit her job with advertising agency FCBUlka in Mumbai and spent most of her time in Udaipur, where the lake water was no match for the cold she would encounter in the Earth’s southernmost continent. So, she added 15-20 tonnes of ice in a large tub and suspended herself into it for hours. This went on for 10 days till she realised it could have adverse implications on her health, including putting stress on the heart.

2019 W-Power Trailblazers list

Despite intense preparations, she was all at sea in the Antarctic during the initial few minutes. The water was far from friendly. “I was ready for the cold, but the water felt heavy because of the melting glaciers. It was dark and greyish, and the salt content was high. It was like pulling through oil,” reminisces Sharma. “For the first few minutes, I thought I won’t be able to do it. But my mental training helped. I decided to take it one stroke at a time.”

Yoga strengthened her mind. While in Udaipur, she meditated and spoke to her teacher (an elderly relative) to dispel doubts and fears that kept creeping in her head. The result was breaking a previous record (of covering 1.6 km in 18 minutes and 10 seconds) set by Britain’s Lewis Pugh in December 2005 at the age of 36. It won her praise from Prime Minister Narendra Modi too. Sharma also found an unlikely supporter during that swim: A penguin. “After about 10 minutes into the water, I saw it go under my stomach. I took it as my personal cheerleader,” she says.

Encounters with stingrays, sea lions and jelly fish have given Sharma a glimpse of marine life up close. In fact, during her 2007 swim of the Strait of Gibraltar in the Mediterranean Sea off Spain, she saw a fin to her right. By the time she completed a stroke and looked again, it wasn’t visible. “I thought I had imagined it,” says Sharma, who goes through a range of emotions during her long swims and sings Bollywood songs to entertain herself. Her mother told her after the swim that a fin whale was indeed by her side for a short while.

Such experiences romanticise the nature of the sport, but they often hide its ugly realities. Lack of acknowledgement for swimming in the country and paucity of financial support are major roadblocks that Sharma points to. “Swimming itself is not the main sport in India,” she rues.

Until her Gibraltar expedition, her family took care of the expenses and logistics. “I am their investment,” says Sharma, who loves travelling to new places. She found partial sponsorship from Hindustan Zinc, a Vedanta Group company, for her Antarctica swim, apart from relying on crowdfunding.

Leena claims they have spent crores on the expeditions and got less than 50 percent in sponsorships. A common refrain from those she approached for monetary assistance: Why doesn’t she compete in the Olympics instead of doing all this?

Sharma’s father Chandra Shekhar worked for a watch factory in Mumbai before moving to Udaipur to start a marble business. Leena was chief cashier with Bank of India who took voluntary retirement in 2009. They lived in a one-bedroom flat in Udaipur and rented eight homes before buying their own house. “We, as a family, have grown together,” says an emotional Sharma, who aspires to be a successful businessperson.

Sharma went to the US with the intention of training for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. “But I miscalculated the time and energy that it takes. I have not been able to train as much, partly because I am also a teaching assistant and that takes up a lot of my time. This comes with the struggle of not having a sponsor,” she laments, before adding that she will strive hard to compete in the Games.

Sharma sees her achievements as merely meeting the targets that she had set for herself. “Till the Arctic swim, I did not realise the gravity of what I had done. But it has definitely given me a voice at different levels,” says Sharma, referring to the various platforms where she is often invited to narrate her story and encourage young girls to take up the sport.

The tide, she hopes, will turn one day.

First Published: Mar 06, 2019, 11:47

Subscribe Now