India's $10 trillion target

Only the United States and China have $10 trillion-plus economies. What it will take for India to get there

Illustrations: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurIn February, while presenting the Union Budget, a brief reference to the future size of the Indian economy by interim finance minister Piyush Goyal got people to sit up, take notice, and either nod appreciatively or scoff at his claim. “We are poised to become a $5 trillion economy in the next five years and aspire to become a $10 trillion economy in the next eight years thereafter,” said Goyal. $10 trillion is the equivalent of ₹705,00,00,000 lakh crore at current exchange rates.

Illustrations: Chaitanya Dinesh SurpurIn February, while presenting the Union Budget, a brief reference to the future size of the Indian economy by interim finance minister Piyush Goyal got people to sit up, take notice, and either nod appreciatively or scoff at his claim. “We are poised to become a $5 trillion economy in the next five years and aspire to become a $10 trillion economy in the next eight years thereafter,” said Goyal. $10 trillion is the equivalent of ₹705,00,00,000 lakh crore at current exchange rates.

Expectedly, most disagreements were with the ambitious timeline Goyal had proposed—getting there would require 11.36 percent growth a year for the next 13 years–but this marked an important shift. It was the first time the government seemed to have a number in mind. Later that month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi followed it up by saying that the Indian economy would reach $10 trillion. He did not specify a timeline.

Given India’s current growth trajectory, the significant catch-up growth left, and the country’s favourable demographics, getting to $10 trillion is a fair bet to take. Last year, Forbes India had explained to readers why, in the absence of a rising savings rate, slow growth in productivity and lack of reform in factor markets—land, labour and capital—it is unlikely India will reach a 9 percent-plus growth trajectory in the next few years.Manish Chokhani, director at brokerage Enam Holdings, cautions, “The past is replete with examples of countries that have failed to live up to their potential, including India.” Yet, there are slivers of hope. A recent study by McKinsey Global Institute titled Outperformers: High- growth emerging economies and the companies that propel them, which looked at 71 economies, classified India as a recent outperformer—or an economy that has grown at 5 percent or more for over 20 years.

At its current growth trajectory of about 7 percent, McKinsey expects the country to hit $5 trillion in 2025 and $10 trillion sometime in the 2030s in nominal terms. Anu Madgavkar, partner at the McKinsey Global Institute, reckons India’s growth is likely to be more stable as it is not a resource-dependent economy in terms of GDP structure. Brazil and Russia have both suffered growth shocks in the last seven years, as the prices of oil and iron ore have plunged even as India and China (net commodity importers) weathered high prices.

Powering Growth

One of the peculiarities about India’s growth record is that it is the only large global economy that has grown without a significant manufacturing base. Policy makers have tried to address this, with the ‘Make In India’ initiative attempting to attract manufacturing investments. Its success has been patchy at best—industry accounts for 26 percent of GDP, way behind services’ 58 percent—and there is now a view that India’s policymakers should not try and emulate the time tested path of moving first to manufacturing and then to service-led growth. “I am sure that if India suddenly became a big successful manufacturing economy, it would make it (the path to $10 trillion) a lot easier, but I am not at all convinced that India will or should, given its own idiosyncrasies,” says Jim O’Neill, chair at Chatham House and former chief economist at Goldman Sachs where he authored the BRCIS report. Missing the manufacturing bus could prove a boon in hindsight research by economist Dani Rodrik at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University has shown that premature de-industrialisation is hitting developing countries at lower levels of income. Madgavkar of McKinsey believes that India’s manufacturing peak could come at a per capita income level of $5,500, roughly 2.5 times today’s level of $2,045 level.

“I am sure that if India suddenly became a big successful manufacturing economy, it would make it (the path to $10 trillion) a lot easier, but I am not at all convinced that India will or should, given its own idiosyncrasies,” says Jim O’Neill, chair at Chatham House and former chief economist at Goldman Sachs where he authored the BRCIS report. Missing the manufacturing bus could prove a boon in hindsight research by economist Dani Rodrik at the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University has shown that premature de-industrialisation is hitting developing countries at lower levels of income. Madgavkar of McKinsey believes that India’s manufacturing peak could come at a per capita income level of $5,500, roughly 2.5 times today’s level of $2,045 level.

While the peak is still some way off, it’s possible that India could be the first major economy without a large manufacturing base. Consumption (services) and increased spending on infrastructure would drive growth then. At about 5 percent of GDP, India’s current spending on infrastructure needs to move up.

Its present savings rate and access to global capital could take it up to 6-7 percent of GDP. But the $5trillion investment in infrastructure number that is often spoken about would require 9 percent of GDP spending sustained for a decade. This has the potential to create employment and India has what Chokhani calls a “once in a lifetime opportunity to access a glut of global capital-seeking stable returns in a growth market.” The last five years have seen long-term investment from a host of global pension funds in India’s roads, ports and bridges. With interest rates likely to stay low, expect more such yield-seeking investments making their way to India. Private sector investments will be another significant albeit smaller boost.

Holding up the economy would be Indian’s consumption basket that has (the recent slowdown not withstanding) proved resilient over the last two decades. While China struggles to make domestic consumption account for 40 percent of its economy, India already has two-thirds of growth coming from this engine. Add to this the fact that the Indian consumer has only in the last decade started leveraging her personal balance sheet and there is a chance that the consumption engine will continue to hum along.

Growth Risks

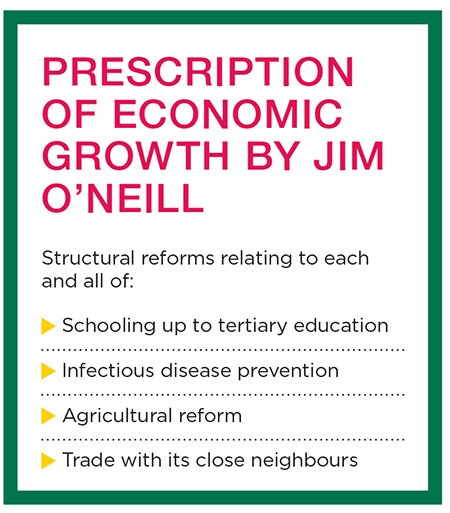

While catch up growth, favourable demographics and a workforce that can speak English will get India moving, the risks to the story come from India’s poor record of not being able to provide basic education and health services. O’Neill says these are prerequisites for higher growth and it is disappointing that governments have not focused on this. He cites the examples of China and South Korea that have done this successfully. China’s huge success has been in improving education in urban areas while in South Korea the improvements have been broad-based, allowing the country to leapfrog in a generation and move up from sub-Saharan levels of wealth to those of Spain and Portugal. For now it remains to be seen if the path to $10 trillion gets hindered on account of the lack of spending. The government has tried to address these shortcomings in a piecemeal manner – school vouchers for underprivileged children and a health insurance scheme for the less well off. Expect to see more experiments in both these spaces.

For now it remains to be seen if the path to $10 trillion gets hindered on account of the lack of spending. The government has tried to address these shortcomings in a piecemeal manner – school vouchers for underprivileged children and a health insurance scheme for the less well off. Expect to see more experiments in both these spaces.

Another possible pitfall is the tendency among policy makers to get into a competitive distributive mindset. India has schemes for everything from free bicycles and laptops to cheap rice and increasingly cash transfers to farmers whose holdings are under a certain size. The world over economies have expanded the social net as they’ve grown richer. And there is little doubt that it will happen in India as well. Brazil did it in the 1970s and 1980s when tax revenues were buoyant.

India started with the rural employment guarantee scheme in 2005 and tax buoyancy allowed the government to easily pay for it. Although this is hotly contested, the scheme did create productive assets (ponds, roads, irrigation canals) in rural India. The present rounds of distributive transfers being proposed will, in all likelihood, drive up consumption spending without the productive base to support it. It remains to be seen if an excess income transfers spur inflation and trip up growth.

Lastly, there’s defence. A richer India would need to up spending to counter its neighbors China and Pakistan. In 2018 the allocation moved up to $52 billion, up 9.7 percent a year over the last decade. This compares poorly with the $146 billion China spent and there is every likelihood that the number is going to rise. One way to stop defence spending spiraling out of control is for India to increase trade with its neighbours. Trade with Pakistan is a paltry $2 billion, and a recent World Bank study reckoned it could go up to $37 billion if there was more trust between the two countries. As for China-India trade, it is largely skewed, with India’s exports less than half of its imports from China, worth $76.2 billion in 2017-18. China, of late, has shown keenness to increase imports from India, and in that may well lie an opportunity not just for a better balance of trade but for defusing pent-up tensions.

First Published: May 10, 2019, 07:48

Subscribe Now