How Meg Whitman Designed Hewlett-Packard's Revival Strategy

Two years into an epically challenged tenure, Meg Whitman may yet emerge as the best CEO HP has had since the founder days of Bill and Dave

To understand what Meg Whitman, the former eBay chief executive who now runs Hewlett-Packard, is up to, it’s essential to revisit something she did 26 years ago. She had just become a junior partner at Bain Consulting, working for the brilliant but domineering Tom Tierney. One morning Whitman walked into his office, impromptu. The 31-year-old asked her feared boss if he wanted staff feedback about his leadership style he nodded. With that, Whitman grabbed a felt-tip marker and sketched a giant steamroller on a nearby whiteboard. “This is you, Tom,” she explained. “You’re too pushy—you’re not letting us build consensus leadership.”

Tierney was stunned. But he eventually absorbed the message and toned down his stridency. All of Bain beneï¬ted. “There was a real courage to her,” recalls Tierney. “What she told me was a gift. Even though her feedback was negative and unsolicited, it left me liking Meg more.”

Jump ahead to last year, soon after a boardroom uprising brought Whitman to power as HP’s chief executive. She stepped into a mess: HP’s stock had tumbled 42 percent in the year before she took office, while operating margins had sunk to just 2.5 percent. Arch rival Dell was gaining ground in the server market, and HP seemed powerless to stop it. When the two computer makers vied for a $350 million server order from Microsoft’s Bing search engine team in April 2012, Dell won the job. Familiar story: Bing’s previous four face-offs had all gone Dell’s way, too.

Whitman refused to shrug off defeat. Within minutes, she was on the phone to Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer, demanding the same candour she once offered Tierney. “Tell me where we came up short,” Whitman asked. “Don’t sugarcoat it. I’d like to know so that we can do better the next time.” Soon afterwards, Microsoft sent a multipage memo to Whitman, listing nine ways that HP had fumbled its opportunity. “Even if your bid had been price-competitive, you wouldn’t have won,” a Microsoft lieutenant declared.

For Whitman, the memo wasn’t an insult it was a battle plan. She convened a war team of HP’s enterprise computing chief, Dave Donatelli the company’s operations chief, John Hinshaw and supply chain wizard Tony Prophet. Their job: Figure out how to make HP more competitive. Match Dell’s ability to suggest cost-saving steps that hadn’t occurred to Microsoft. Done. Promise to ï¬x software bugs in two days, not four weeks. HP was on it. By summer, HP had crafted a far more customer-friendly approach. When Bing bought a further $530 million of servers in January, vindication arrived. This time HP, not Dell, seized the order.

Blunt, folksy and persistent, Meg Whitman is the leader that Hewlett-Packard desperately needs. She’s decisive without being abrasive, persuasive without being slick. She’s a team builder who knows that turnarounds call for repairing hundreds of small failings rather than betting everything on a miracle cure that might be a mirage. In the words of HP director Marc Andreessen, one of Silicon Valley’s top venture capitalists, “She’s the best CEO the company has had since its founders.”

But ï¬xing the world’s biggest tech company—with $120 billion in annual revenue and 330,000 employees—is a Herculean task. Bloated by more than 70 acquisitions in the past 15 years, HP isn’t just sprawling and stalled out it may actually be running in reverse. Revenue has been shrinking for most of the past seven quarters. HP’s return on capital is a pitiful 7 percent over the past ï¬ve years. (By comparison, IBM is at 29 percent, and even Dell, which has its own troubles, is at 24 percent.) HP is still proï¬table before its enormous asset writedowns, but with its stock trading at a feeble price/earnings multiple of six, one major investor suggests HP can’t totally shake the fear that it might go to zero.

Too gruesome for Whitman’s tastes? Guess again. “Problems are good, as long as you solve them quickly,” says Whitman over a Cobb salad lunch at HP’s facilities, now chock-a-block with posters of Whitman’s favourite sayings, including this aphorism: “Run to the ï¬re don’t hide from it.” “Meg thrives on these sorts of challenges,” says Howard Schultz, the Starbucks CEO and a longtime friend who has known her since their time together on the eBay board.

When Whitman took command 20 months ago, following her own hiccup—a personally expensive thumping in the 2010 election for governor of California—she walked into a company that had squeezed out its previous four CEOs. In 1999, genial insider Lew Platt didn’t deliver enough sizzle, charismatic marketer Carly Fiorina couldn’t hit earnings targets in 2005, and hard-nosed numbers guy Mark Hurd got tangled up in an expense-account scandal in 2010. Whitman’s immediate predecessor, aloof European import Léo Apotheker, lasted just 11 months. His undoing: Ill-advised strategic thrusts that sent HP’s stock crashing.

Nobody on HP’s board wanted the hazards of trying to pick and train another total outsider. Internal candidates were scarce. So in August 2011, as Apotheker’s stormy tenure neared its end, directors began to coalesce around Whitman as their best choice. She had been a successful Silicon Valley CEO. She had joined the HP board in January 2011 and was well aware of the company’s challenges. And with Jerry Brown ensconced in the governor’s mansion in Sacramento, she was available for a new full-time job.

One problem: Whitman didn’t want the gig. She told HP directors Raj Gupta and Andreessen that she would be busy enough with board work, private equity and perhaps an appointed political post. “I’m done running companies,” she told one board member. But on a private-jet flight back to the Bay Area after an HP board meeting, other directors began lobbying her. They invoked HP’s extraordinary heritage as Silicon Valley’s ï¬rst garage startup, begun in 1939 by engineers Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard. They talked about how important HP was to the California economy and as a global symbol of innovation.

“Suddenly the conversation changed to what she might do if she took the job,” Andreessen recalls. “I saw this twinkle in her eye. And I said to myself: ‘I think we got her.’”

The tech sector, Whitman well knows, is unusually stingy with second chances. Fall behind and you die. The two great exceptions date back to the 1990s: Steve Jobs’ resurrection of Apple and Lou Gerstner’s transformation of IBM. Asked about those templates, the 56-year-old Whitman quickly rules out a Jobs comparison. “Steve was the business genius of our generation,” she says. “It’s hard for anyone to emulate him.” Besides, no magical iPod or iPhone beckons in HP’s future. The Gerstner turnaround, by contrast, “is probably more relevant”, she says.

Like the outsider who got Big Blue back on track, Whitman started her ï¬rst board meeting as CEO in October 2011 by declaring: “Rule number one is to ï¬x what we have.” She reversed Apotheker’s plans to sell off the PC business at what would have likely been a ï¬re-sale price. She believed that business could be ï¬xed, especially if it focussed harder on the booming market for tablets and other mobile devices. And she stuck with Apotheker’s proposed purchase of British software company Autonomy for $11 billion, which backï¬red.

To keep things simple, Whitman has arranged HP into two clusters. One grouping aims at corporate tech customers, led by Donatelli’s enterprise hardware shop. Its servers, storage and networking delivered 43 percent of overall operating proï¬ts in the most recent quarter. In theory, all this iron and silicon should be buttressed by adjoining software and services divisions. But when it comes to software acquisitions, Autonomy was merely the most high-proï¬t misstep. All told, over the past decade HP squandered nearly $19 billion to buy myriad outï¬ts that contribute only 7 percent to overall proï¬t. The services unit, which staffs other companies’ tech projects, is barely at break-even. It is trying to rebuild after a $8 billion writedown last August.

HP’s other cluster sells printers, PCs, laptops and mobile devices, chiefly to consumers worldwide. Unfortunately for Whitman, the days of being able to rely on the lucrative printer business for outsize proï¬ts are over. (In 2002, printing actually contributed 104 percent of HP’s total operating proï¬ts because everything else was below break-even today that contribution is only 29 percent.) Corporations still buy lots of printers and ink, but consumers’ appetites have dimmed. The likes of Google, Facebook and Dropbox have facilitated a burgeoning era of ink-free photo- and document-sharing.

To get both of HP’s legacy businesses moving, Whitman started by overhauling how the company sells. Internal surveys showed that HP’s more than 20,000 salespeople rated their own in-house sales tools at about a 7—on a scale of 1 to 100. It took HP as long as three weeks to work up a price quote on a complex order. Competitors could do the same in a few days. Many customers chafed. Others just looked elsewhere. When Whitman’s operations chief, John Hinshaw, recommended yanking out Oracle’s ageing Siebel sales software in favour of new salesforce.com tools, she gave him the go-ahead to get the company converted as fast as possible. HP’s price-quote queue has shrunk 75 percent, while those internal metrics have soared into the 70s. Sellers’ ulcers are gone, and customer rapport is on the mend.

Along with timelier terms, HP’s customers need reassurance that the company knows what it’s doing. At the end of the Apotheker era, “We were quite concerned that HP wasn’t well glued together,” recalls Dana Deasy, group chief information officer at oil giant BP.

So Whitman hit the road. In the past year, she has held a staggering 305 one-on-one meetings with customers or sales-channel partners, aides say, as well as another 42 roundtable chats with small groups. A peek at her calendar the past 60 days shows trips to Munich, London, Brazil, India, New York and Bentonville, Arkansas, the home of Walmart. “She’s made herself more available than her predecessor ever did,” says Chris Case, president of Sequel Data Systems in Austin, Texas.

Jim Fortner, an IT executive at Procter & Gamble, says he quizzed Whitman at length last year about HP’s personal computer strategy. He was relieved to get consistent answers. “That’s important for us,” Fortner says. “We buy a lot of PCs.” BP’s Deasy says that during one of Whitman’s London visits, he griped about an HP software installation that wasn’t happening on time. She made some calls and discovered a fractured team that didn’t hold anyone accountable for speedy delivery. The project, Deasy reports, is now back on track.

As Bain’s Tom Tierney learned the hard way, Meg Whitman is fond of making her points graphically. As I push her on HP’s long-term challenge—how to get her company’s growth engines ï¬ring again—she reflexively grabs a sheet of paper. “You’ve got to start launching new products when your existing ones are still growing,” she says. “It is not helpful to start a new product here,” as she points to the downward slope of a sales curve that crested too long ago.

The result, Whitman says, “is that we’ve got acorns when we need oak trees”. She can’t make up ground through acquisitions: The stock is too cheap, Wall Street too hostile given the spendthrift track record, and HP is trying to reduce last year’s $5.8 billion operating company debt to zero.

Instead, Whitman needs to heap fertiliser onto those acorns—fast. Products with the most promise include Moonshot servers, which are small, energy-efficient and flexible 3PAR storage devices, which can go up and down in size without busting budgets and its inkjet ofï¬ce printers, which match the speed and quality of laser printers at a much lower cost. But even in these areas it’s tough to see marginal revenue growth outpacing the sales deterioration of tired old products.

The acorn/oak tree problem is especially acute in the fast-growing tablet market. HP should dominate in the same way that it has become the world’s biggest maker of PCs and laptops. But HP’s tablet strategy for years has been a baffling mix of launches and retreats, culminating with Apotheker’s August 2011 decision to kill the TouchPad model introduced just seven weeks earlier.

Belatedly, HP has jumped back into the hunt. Since February, new models have been streaming into the market, most notably the Slate 7, priced at $169—less than Amazon’s Kindle Fire HD. More machines are about to hit the market, and tech reviewers have generally liked HP’s efforts so far. Still, once market leaders are set, it’s very hard to barrel past them.

HP faces a similar challenge in the server market. Its industry-standard machines, based on Intel chip designs, have been big sellers since the early ’90s. But cutting-edge customers like Google and Rackspace now prefer to build their own servers, arranging parts in the most optimal way for their needs. The new Moonshot server line is attracting interest from banks and energy companies, which like its compact design and ability to run many different types of microprocessors. But the data-crunching tech giants, which buy more servers than anyone, may be gone for good as HP customers.

Previous CEOs hoped that big ad campaigns would make HP seem cool again. Whitman’s brand messaging, centred on the motto “Make It Matter”, seems most likely to bolster the spirits of HP’s workforce. For wooing the public at large, she is taking a page out of Jobs’ playbook. “Look at Apple,” says Whitman, referring to its design. “Or look at websites like Zaarly, Path or One Kings Lane. When I got involved in the internet in the 1990s, websites weren’t beautiful. Now they are. Design is a differentiating characteristic in our markets. We need to take advantage of that.”

So HP now has an overall vice-president for design, Stacy Wolf, who oversees a fast-growing 40-person team of recruits from the likes of BMW, Nokia and Frog Design. A new, big-screen, all-in-one PC has a nifty hinge that holds its tilt at any viewing angle power buttons on PCs and printers now glow the same green colour even perforated cooling grilles look sleeker yet more friendly. It’s not quite Apple-elegant, but it no longer looks like metal shop either.

Whitman, a Harvard MBA with an economics degree from Princeton, might not have engineering chops or her name on any patents, but unlike HP’s previous three CEOs, she is Silicon Valley informal through and through. When she joined eBay in 1998, the then-tiny auction company was deï¬ned by the sweet, New Ageish values of the company’s founder, Pierre Omidyar: Change the world, have fun, believe that most people are good. Whitman ï¬gured out how to combine his vision with big-league business practices that let eBay enjoy sustainable hypergrowth. She worked marathon hours at one stage, rebuilding eBay’s technical team until the site could handle booming traffic. But she also embraced the jokey, college-dorm atmosphere of an ambitious startup, ï¬lling her desk with goofy eBay auction items and dressing up as a witch one Halloween.

So the new HP attitude starts at the front door of its low-slung Palo Alto headquarters. She dumped the barbed wire and locked gates that once separated executive parking spaces from the general lot. “We should enter the building the same way everyone else does,” she says. Once inside, Whitman works from a small, sand-coloured cubicle. (Her predecessors’ sombre office has been turned into a conference room.) She has a swim cap tacked to one partition, a picture of her mom on another. A Thomas Jefferson biography tops the heap of books next to her computer.

Management tracts reside in the middle, treatises on cloud computing on the bottom. On the road, she often settles for a $139 room at the Courtyard Marriott, despite being worth $1.9 billion. “You check in at 10 pm, and you’re out at 7 am,” she shrugs. It’s also a painless and visible way to lead by example.

But her tough, hands-on streak, often displayed at eBay and bolstered by two years of taking and throwing vicious political haymakers, comes through when things go wrong. Her printing team’s weak explanation, in a three-hour meeting, of why their business kept falling short of ï¬nancial goals led to two marathon brainstorming sessions, where she focussed on hard-to-spot bad habits like excessive use of rebates. By the time Whitman was done, the printing team had a new cap on rebates—and a new division boss to enforce it.

And Whitman has picked a ï¬ercer ï¬ght against Autonomy’s original management team. Last November, HP took a $8.8 billion charge in connection with that purchase, blaming the setback on “serious accounting improprieties” in Autonomy’s books at the time of sale. Autonomy founder Mike Lynch instantly disputed that claim, blaming HP instead for poorly managing its new acquisition. He declined to comment for this story.

Ongoing arguments have kept the Autonomy mess in the news, but as HP presses authorities in the US and UK to investigate fraud claims, its willingness to ï¬ght sits a lot better with employees than watching the management shrug off another blunder and hoping it fades from memory. Almost 80 percent of HP employees at Glassdoor.com, a website packed with anonymous feedback, say they have conï¬dence in Whitman, placing her in a tie with IBM’s Virginia Rometty and slightly ahead of corporate stalwarts such as Cisco’s John Chambers (76 percent).

Whitman has more work to do to win over Wall Street. She warned investors and her board early on that getting HP back on track would be a ï¬ve-year job, deï¬ning 2013 as a “ï¬x and rebuild” year, with no assurances of sustained growth until 2014. When ï¬scal ï¬rst-quarter results topped analysts’ scaled-down expectations, she spoke of “a long road ahead”.

If Whitman can lift the doomsday anxiety, HP’s shares could roar ahead. “Meg and the team are delivering everything they said they would,” says Pat Russo, an HP director and the former CEO of Alcatel-Lucent. “We are committed to her.” Adds fellow director Raj Gupta, the former CEO of Rohm & Haas: “As long as she’s enjoying it and the company is on track, the board would like to see her stay as long as she wants.”

Whitman is beyond ï¬nancial motivation. She’s playing for legacy: “There’s quite a bit of pride in being part of something that means so much to the Valley and to this country. It’s a nice company. Nice people. And I think we’re going to turn this.”

HP AND THE STONE-THROWERS

When big companies stumble, activist investors storm into the picture. For Dell, it’s Carl Icahn demanding a new CEO.

For Sony, a transpaciï¬c hounding from Dan Loeb. Even Apple earned a tongue-lashing from David Einhorn about its dividend policy. So why haven’t the stone-throwers come after Hewlett-Packard?

The answer: Meg Whitman and HP’s Chief Financial Officer Cathie Lesjak struck a quick truce in November 2011 when activist investor Ralph Whitworth of Relational Investors proposed that he join the HP board. His agenda called for a more careful approach to capital spending, and the HP leaders embraced that. As Lesjak recalls, “We walked out of the room and said: ‘Wow, we like the way he thinks.’&thinsp”

Whitworth has jousted with other companies’ management in the past, but by public appearances all is lovely between him and HP. When HP director Ray Lane stepped down as chairman this April, Whitworth took over the chair on an interim basis. Whitworth announced his new status in an upbeat HP blog, declaring: “I walk away from every interaction more conï¬dent about this company’s future.”

Whitworth will want to cash out at some point, and other activists may pound the table for aggressive agendas. But Lesjak, a 24-year-veteran of HP, is betting that candour and civility will carry the day. “When we talk to investors it’s all about communication, communication,” she says. “Things won’t always play out exactly the way you want. You just have to put everything on the table.” —GA

ENTREPRENEURS CLINIC

As a CEO in the hot seat, Meg Whitman constantly hears the clock ticking on the HP turnaround. She has plenty of advice for entrepreneurs who are short of time—and unseasoned when it comes to time management

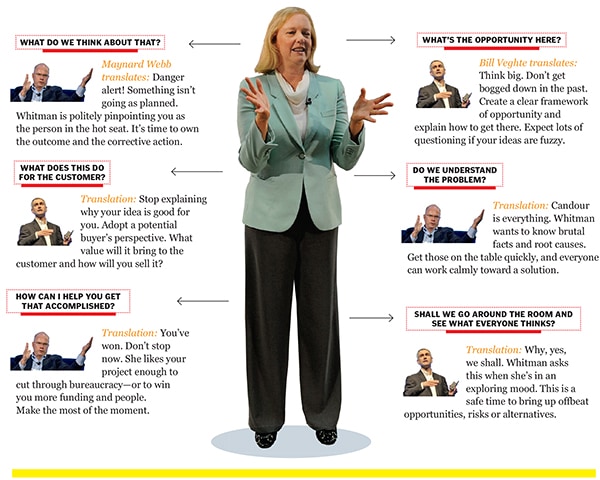

Concentrate on your strengths.

I try to ï¬gure out what I’m uniquely good at—and surround myself with people who are really good at what I’m not good at. My partnership with former eBay CTO Maynard Webb was perfect—one plus one equalled seven. At HP, Bill Veghte, the COO, and I have a very good complementary partnership. Having grown up in the enterprise, he knows it incredibly well and is deep from a technology perspective. I’m very good on strategy, market segmentation, communications and leading the charge.

Recalibrate Your Priorities weekly.

I constantly check the to-do list. Every Sunday night I ask myself: What do we have to get done? What did we think was important last week? What can go away? If a new priority is more important than an older one, how are we going to get there from here? With my calendar on my laptop, I go out three or four months—and work backwards.

Walk Away From Gridlock.

If we’re off on a really bad tangent, I’ll hand a project back to the team. Even though there is a piece of me that thinks, “If I spend another ï¬ve hours on this I’m sure I could make a difference.” I’m always looking for the

right person to solve a problem. I only have so much time.

NEXT

I keep meetings under control because I’m literally scheduled back-to-back from 9 am until 6 pm. That’s a natural forcing function that prevents things from running over.

Measure The Right Things.

We spent some time asking, “What are the things we need to measure?” Customer loyalty, on-time product launches, percentage of volume through the channel, average selling prices, attach rates of software to hardware and so forth. The result is the dashboards we’ve developed. I get them once a week, and they’re pretty helpful because, as the adage goes, you focus on what you measure. They serve as early-warning indicators: If you start to see things going south, then you can get in front of them.

It’s a roadmap that will help us run the company.

First Published: Jun 25, 2013, 06:45

Subscribe Now