How a 'Deviant' Philosopher Built Palantir, a CIA-Funded Data Miner

How a self-described "deviant" philosopher turned Palantir into a terrorist-tracking, all-seeing, multibillion-dollar data-mining machine

Since rumours began to spread that a startup called Palantir helped to kill Osama bin Laden, Alex Karp hasn’t had much time to himself.

On one sun-baked July morning in Silicon Valley, Palantir’s lean 45-year- old chief executive, with a top-heavy mop of frazzled hair, hikes the grassy hills around Stanford University’s massive satellite antennae known as the Dish, a favourite meditative pastime. But his solitude is disturbed somewhat by “Mike”, an ex-Marine— silent, 6 foot 1, 270 pounds of mostly pectoral muscle—who trails him everywhere he goes. Even on the suburban streets of Palo Alto, steps from Palantir’s headquarters, the bodyguard lingers a few feet behind.

“It puts a massive cramp on your life,” Karp complains, his expression hidden behind large black sunglasses. “There’s nothing worse for reducing your ability to flirt with someone.”

Karp’s 24/7 security detail is meant to protect him from extremists who have sent him death threats and conspiracy theorists who have called Palantir to rant about the Illuminati. Schizophrenics have stalked Karp outside his office for days at a stretch. “It’s easy to be the focal point of fantasies,” he says, “if your company is involved in realities like ours.”

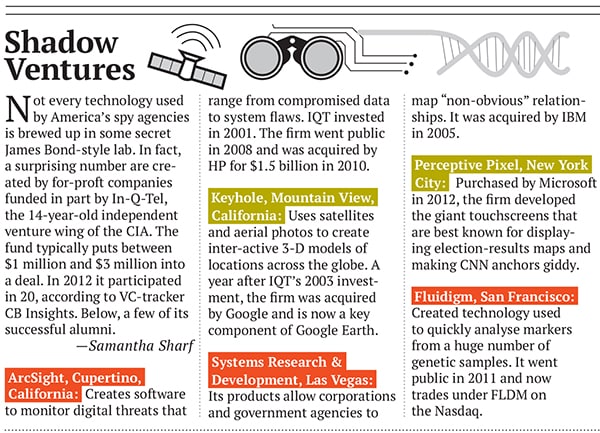

Palantir lives the realities of its customers: The NSA, the FBI and the CIA—an early investor through its In-Q-Tel venture fund—along with an alphabet soup of other US counterterrorism and military agencies. In the last five years Palantir has become the go-to company for mining massive data sets for intelligence and law enforcement applications, with a slick software interface and coders who parachute into clients’ headquarters to customise its programs. Palantir turns messy swamps of information into intuitively visualised maps, histograms and link charts. Give its so-called “forward-deployed engineers” a few days to crawl, tag and integrate every scrap of a customer’s data, and Palantir can elucidate problems as disparate as terrorism, disaster response and human trafficking.

Palantir’s advisors include Condoleezza Rice and former CIA director George Tenet, who said in an interview that “I wish we had a tool of its power” before 9/11. General David Petraeus, the most recent former CIA chief, describes Palantir to Forbes as “a better mousetrap when a better mousetrap was needed” and calls Karp “sheer brilliant”.

Among those using Palantir to connect the dots are the Marines, who have deployed its tools in Afghanistan for forensic analysis of roadside bombs and predicting insurgent attacks. The software helped locate Mexican drug cartel members who murdered an American customs agent and tracked down hackers who installed spyware on the computer of the Dalai Lama. In the book The Finish, detailing the killing of Osama bin Laden, author Mark Bowden writes that Palantir’s software “actually deserves the popular designation Killer App.”

And now Palantir is emerging from the shadow world of spies and special ops to take corporate America by storm. The same tools that can predict ambushes in Iraq are helping pharmaceutical firms analyse drug data. According to a former JPMorgan Chase staffer, they’ve saved the firm hundreds of millions of dollars by ad- dressing issues from cyberfraud to dis- tressed mortgages. A Palantir user at a bank can, in seconds, see connections between a Nigerian internet protocol address, a proxy server somewhere within the US and payments flowing out from a hijacked home equity line of credit, just as military customers piece together fingerprints on artillery shell fragments, location data, anonymous tips and social media to track down Afghani bombmakers.

Those tools have allowed Palantir’s T-shirted twenty-somethings to woo customers away from the suits and ties of IBM, Booz Allen and Lockheed Martin with a product that deploys faster, offers cleaner results and often costs less than $1 million per installation—a fraction of the price its rivals can offer. Its commercial clients—whose identities it guards even more closely than those of its government customers—include Bank of America and News Corp. Private-sector deals now account for close to 60 percent of the company’s revenue, which Forbes estimates will hit $450 million this year, up from less than $300 million last year. Karp projects Palantir will sign a billion dollars in new, long- term contracts in 2014, a year that may also bring the company its first profits.

The bottom line: A CIA-funded firm run by an eccentric philosopher has become one of the most valuable private companies in tech, priced at between $5 billion and $8 billion in a round of funding the company is currently pursuing. Karp owns roughly a tenth of the firm—just less than its largest stakeholder, Peter Thiel, the PayPal and Facebook billionaire. (Other billionaire investors include Ken Langone and hedge fund titan Stanley Druckenmiller.) That puts Karp on course to become Silicon Valley’s latest billionaire—and Thiel could double his fortune—if the company goes public, a possibility Karp says Palantir is reluctantly considering.

The biggest problem for Palantir’s business may be just how well its software works: It helps its customers see too much. In the wake of NSA leaker Edward Snowden’s revelations of the agency’s mass surveillance, Palantir’s tools have come to represent privacy advocates’ greatest fears of data-mining technology—Google- level engineering applied directly to government spying. That combination of Big Brother and Big Data has come into focus just as Palantir is emerging as one of the fastest-growing startups in the Valley, threatening to contaminate its first public impressions and render the firm toxic in the eyes of customers and investors just when it needs them most.

“They’re in a scary business,” says Electronic Frontier Foundation attorney Lee Tien. ACLU analyst Jay Stanley has written that Palantir’s software could enable a “true totalitarian nightmare, monitoring the activities of innocent Americans on a mass scale”.

Karp, a social theory PhD, doesn’t dodge those concerns. He sees Palantir as the company that can rewrite the rules of the zero-sum game of privacy and security. “I didn’t sign up for the government to know when I smoke a joint or have an affair,” he acknowledges. In a company address he stated, “We have to find places that we protect away from government so that we can all be the unique and interesting and, in my case, somewhat deviant people we’d like to be.”

Palantir boasts of technical safeguards for privacy that go well beyond the legal requirements for most of its customers, as well as a team of “privacy and civil liberties engineers”. But it’s Karp himself who ultimately decides the company’s path. “He’s our conscience,” says senior engineer Ari Gesher.

The question looms, however, of whether business realities and competition will corrupt those warm and fuzzy ideals. When it comes to talking about industry rivals, Karp often sounds less like Palantir’s conscience than its id. He expressed his primary motivation in his July company address: To “kill or maim” competitors like IBM and Booz Allen. “I think of it like survival,” he said. “We beat the lame competition before they kill us.”

Karp seems to enjoy listing reasons he isn’t qualified for his job. “He doesn’t have a technical degree, he doesn’t have any cultural affiliation with the government or commercial areas, his parents are hippies,” he says, manically pacing around his office as he describes himself in the third person. “How could it be the case that this person is co-founder and CEO since 2005 and the company still exists?”

The answer dates back to Karp’s decades-long friendship with Peter Thiel, starting at Stanford Law School. They both lived in the no-frills Crothers dorm and shared most of their classes during their first year, but held starkly opposite political views. Karp had grown up in Philadelphia, the son of an artist and a pediatrician who spent many of their weekends taking him to protests for labour rights and against “anything Reagan did”, he recalls. Thiel had already founded the staunchly libertarian Stanford Review during his time at the university as an undergrad.

“We would run into each other and go at it… like wild animals on the same path,” Karp says. “Basically I loved sparring with him.”

With no desire to practice law, Karp went on to study under Jürgen Habermas, one of the 20th century’s most prominent philosophers, at the University of Frankfurt. Not long after obtaining his doctorate, he received an inheritance from his grandfather, and began investing it in startups and stocks with surprising success. Some high-net-worth individuals heard that “this crazy dude was good at investing” and began to seek his services, he says. To manage their money he set up the London-based Caedmon Group, a reference to Karp’s middle name, the same as the first known English-language poet.

Back in Silicon Valley, Thiel had co-founded PayPal and sold it to eBay in October 2002 for $1.5 billion. He went on to create a hedge fund called Clarium Capital but continued to found new companies: One would become Palantir, named by Thiel for the Palantíri seeing stones from JRR Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, orbs that allow the holder to gaze across vast distances to track friends and foes.

In a post-9/11 world Thiel wanted to sell those Palantíri-like powers to the growing national security complex: His concept for Palantir was to use the fraud-recognition software designed for PayPal to stop terrorist attacks. But from the beginning the libertarian saw Palantir as an antidote to—not a tool for—privacy violations in a society slipping into a vise of security. “It was a mission- oriented company,” says Thiel, who has personally invested $40 million in Palantir and today serves as its chairman. “I defined the problem as needing to reduce terrorism while preserving civil liberties.”

In 2004 Thiel teamed up with Joe Lonsdale and Stephen Cohen, two Stanford computer science grads, and PayPal engineer Nathan Gettings to code together a rough product. Initially they were bankrolled entirely by Thiel, and the young team struggled to get investors or potential customers to take them seriously. “How the hell do you get them to listen to 22-year-olds?” says Lonsdale. “We wanted someone to have a little more gray hair.”

Enter Karp, whose European wealth connections and PhD masked his business inexperience. Despite his non-existent tech background, the founders were struck by his ability to immediately grasp complex problems and translate them to non-engineers.

Lonsdale and Cohen quickly asked him to become acting CEO, and as they interviewed other candidates for the permanent job, none of the starched-collar Washington types or MBAs they met impressed them. “They were asking questions about our diagnostic of the total available market,” says Karp, disdaining the B-school lingo. “We were talking about building the most important company in the world.”

While Karp attracted some early European angel investors, American venture capitalists seemed allergic to the company. According to Karp, Sequoia Chairman Michael Moritz doodled through an entire meeting. A Kleiner Perkins exec lectured the Palantir founders on the inevitable failure of their company for an hour and a half.

Palantir was rescued by a referral to In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s venture arm, which would make two rounds of investment totalling more than $2 million. “They were clearly top-tier talent,” says former In-Q-Tel executive Harsh Patel. “The most impressive thing about the team was how focussed they were on the problem… how humans would talk with data.”

That mission turned out to be vastly more difficult than any of the founders had imagined. PayPal had started with perfectly structured and organised information for its fraud analysis. Intelligence customers, by contrast, had mismatched collections of emails, recordings and spreadsheets.

To fulfil its privacy and security promises, Palantir needed to catalogue and tag customers’ data to ensure that only users with the right credentials could access it. This need-to-know system meant classified information couldn’t be seen by those without proper clearances—and was also designed to prevent the misuse of sensitive personal data.

But Palantir’s central privacy and security protection would be what Karp calls, with his academic’s love of jargon, “the immutable log”. Everything a user does in Palantir creates a trail that can be audited.

No Russian spy, jealous husband or Edward Snowden can use the tool’s abilities without leaving an indelible record of his or her actions.

From 2005 to 2008 the CIA was Palantir’s patron and only customer, alpha-testing and evaluating its soft- ware. But with Langley’s imprimatur, word of Palantir’s growing abilities spread, and the motley Californians began to bring in deals and recruits.

A unique Palantir culture began to form in Karp’s iconoclast image. Its Palo Alto headquarters, which it calls “the Shire” in reference to the homeland of Tolkien’s hobbits, features a conference room turned giant plastic ball pit and has floors littered with Nerf darts and dog hair. (Canines are welcome.) Staffers, most of whom choose to wear Palantir-branded apparel daily, spend so much time at the office that some leave their toothbrushes by the bathroom sinks.

Karp himself remains the most eccentric of Palantir’s eccentrics. The lifelong bachelor is known for his obsessive personality: He solves Rubik’s cubes in less than three minutes, swims and practices the meditative art of Qigong daily and has gone through aikido and jujitsu phases that involved putting co-founders in holds in the Shire’s hallways. A cabinet in his office is stocked with vitamins, 20 pairs of identical swimming goggles and hand sanitiser. And he addresses his staff using an internal video channel called KarpTube, speaking on wide- ranging subjects like greed, integrity and Marxism. “The only time I’m not thinking about Palantir,” he says, “is when I’m swimming, practicing Qigong or during sexual activity.”

In 2010 Palantir’s customers at the New York Police Department referred the company to JPMorgan, which would become its first commercial customer. A team of engineers rented a Tribeca loft, sleeping in bunk beds and working around the clock to help untangle the bank’s fraud problems. Soon they were given the task of unwinding its toxic mortgage portfolio. Today Palantir’s New York operation has expanded to a full, Batman-themed office known as Gotham, and its lucrative financial-services practice includes everything from predicting foreclosures to battling Chinese hackers.

As its customer base grew, however, cracks began to show in Palantir’s idealistic culture. In early 2011 emails emerged that showed a Palantir engineer had collaborated on a proposal to deal with a WikiLeaks threat to spill documents from Bank of America. The Palantir staffer had eagerly agreed in the emails to propose tracking and identifying the group’s donors, launching cyber-attacks on WikiLeaks’ infrastructure and even threatening its sympathisers. When the scandal broke, Karp put the offending engineer on leave and issued a statement personally apologising and pledging the company’s support of “progressive values and causes”. Outside counsel was retained to review the firm’s actions and policies and, after some deliberation, determined it was acceptable to rehire the offending employee, much to the scorn of the company’s critics.

Following the WikiLeaks incident, Palantir’s privacy and civil liberties team created an ethics hotline for engineers, called the Batphone: Any engineer can use it to anonymously report to Palantir’s directors work on behalf of a customer they consider unethical. As the result of one Batphone communication, for instance, the company backed out of a job that involved analysing information on public Facebook pages. Karp has also stated that Palantir turned down a chance to work with a tobacco firm, and overall the company walks away from as much as 20 percent of its possible revenue for ethical reasons. (It remains to be seen whether the company will be so picky if it becomes accountable to public shareholders and the demand for quarterly results.)

Still, according to former employees, Palantir has explored work in Saudi Arabia despite the staff’s misgivings about human rights abuses in the kingdom. And for all Karp’s emphasis on values, his apology for the WikiLeaks affair also doesn’t seem to have left much of an impression in his memory. In his address to Palantir engineers in July he sounded defiant: “We’ve never had a scandal that was really our fault.”

At 4:07 pm on November 14, 2009, Michael Katz-Lacabe was parking his red Toyota Prius in the driveway of his home in the quiet Oakland suburb of San Leandro when a police car drove past. A licence plate camera mounted on the squad car silently and routinely snapped a photo of the scene: His single-floor house, his wilted lawn and rosebushes, and his 5- and 8-year-old daughters jumping out of the car.

Katz-Lacabe, a member of the local school board, community activist and blogger, saw the photo only a year later: In 2010 he learned about the San Leandro Police Department’s automatic licence plate readers, designed to constantly photograph and track the movements of every car in the city. He filed a public records request for any images that included either of his two cars. The police sent back 112 photos. He found the one of his children most disturbing.

“Who knows how many other people’s kids are captured in these images?” he asks. His concerns go beyond a mere sense of parental protection. “With this technology you can wind back the clock and see where everyone is, if they were parked at the house of someone other than their wife, a medical marijuana clinic, a Planned Parenthood centre, a protest.”

As Katz-Lacabe dug deeper, he found that the millions of pictures collected by San Leandro’s licence plate cameras are now passed on to the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center (NCRIC), one of 72 federally run intelligence fusion organisations set up after 9/11. That’s where the photos are analysed using software built by a company just across San Francisco Bay: Palantir.In the business proposal that Palantir sent NCRIC, it offered customer references that included the Los Angeles and New York police departments, boasting that it enabled searches of the NYPD’s 500 million plate photos in less than five seconds. Katz-Lacabe contacted Palantir about his privacy concerns, and the company responded by inviting him to its headquarters for a sit-down meeting. When he arrived at the Shire, a pair of employees gave him an hour-long presentation on Palantir’s vaunted safeguards: Its access controls, immutable logs and the Batphone.

Katz-Lacabe wasn’t impressed. Palantir’s software, he points out, has no default time limits—all information remains searchable for as long as it’s stored on the customer’s servers. And its auditing function? “I don’t think it means a damn thing,” he says. “Logs aren’t useful unless someone is looking at them.”

When Karp hears Katz-Lacabe’s story, he quickly parries: Palantir’s software saves lives. “Here’s an actual use case,” he says and launches into the story of a paedophile driving a “beat-up Cadillac” who was arrested within an hour of assaulting a child, thanks to NYPD licence plate cameras. “Because of the licence-plate-reader data they gathered in our product, they pulled him of the street and saved human children lives.”

“If we as a democratic society believe that licence plates in public trigger Fourth Amendment protections, our product can make sure you can’t cross that line,” he says, adding that there should be time limits on retaining such data. Until the law changes, though, Palantir will play within those rules. “In the real world where we work—which is never perfect—you have to have trade-offs.”

And what if Palantir’s audit logs—its central safeguard against abuse—are simply ignored? Karp responds that the logs are intended to be read by a third party. In the case of government agencies, he suggests an oversight body that reviews all surveillance—an institution that is purely theoretical at the moment. “Something like this will exist,” Karp insists.

“Societies will build it, precisely because the alternative is letting terrorism happen or losing all our liberties.”

Palantir’s critics, unsurprisingly, aren’t reassured by Karp’s hypothetical court. Electronic Privacy Information Center activist Amie Stepanovich calls Palantir “naive” to expect the government to start policing its own use of technology. The Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Lee Tien derides Karp’s argument that privacy safeguards can be added to surveillance systems after the fact. “You should think about what to do with the toxic waste while you’re building the nuclear power plant,” he argues, “not some day in the future.”

Some former Palantir staffers say they felt equally concerned about the potential rights violations their work enabled. “You’re building something that could absolutely be used for malice. It would have been a nightmare if J Edgar Hoover had these capabilities in his crusade against Martin Luther King,” says one former engineer. “One thing that really troubled me was the concern that something I contribute to could prevent an Arab Spring-style revolution.”

Despite Palantir’s lofty principles, says another former engineer, its day-to-day priorities are satisfying its police and intelligence customers: “Keeping good relations with law enforcement and ‘keeping the lights on’ bifurcate from the ideals.”

He goes on to argue that even Palantir’s founders don’t quite understand the Palantíri seeing stones in The Lord of the Rings. “The Palantíri distort the truth,” he says. And those who look into them, he adds, “only see what they want to see.”

Despite what any critic says, it’s clear that Alex Karp does indeed value privacy—his own.

His office, decorated with cardboard effigies of himself built by Palantir staff and a Lego fortress on a coffee table, overlooks Palo Alto’s Alma Street through two-way mirrors. Each pane is fitted with a wired device resembling a white hockey puck. The gadgets, known as acoustic transducers, imperceptibly vibrate the glass with white noise to prevent eavesdropping techniques, such as bouncing lasers off windows to listen to conversations inside.

He’s reminiscing about a more carefree time in his life—years before Palantir—and has put down his Rubik’s cube to better gesticulate. “I had $40,000 in the bank, and no one knew who I was. I loved it. I loved it. I just loved it. I just loved it!” he says, his voice rising and his hands waving above his head. “I would walk around, go into skanky places in Berlin all night. I’d talk to whoever would talk to me, occasionally go home with people, as often as I could. I went to places where people were doing things, smoking things. I just loved it.”

“One of the things I find really hard and view as a massive drag … is that I’m losing my ability to be completely anonymous.”

It’s not easy for a man in Karp’s position to be a deviant in the modern world. And with tools like Palantir in the hands of the government, deviance may not be easy for the rest of us, either. With or without safeguards, the “complete anonymity” Karp savours may be a 20th-century luxury.

Karp lowers his arms, and the enthusiasm drains from his voice: “I have to get over this.”

First Published: Sep 16, 2013, 06:36

Subscribe Now